Contents

- 1 ABSTRACT

- 2 Orbital Sovereignty and Strategic Ascendance: India’s Integrated Military-Civilian Space Doctrine in the 21st Century

- 3 India’s Strategic Space Governance: Institutional Frameworks and Global Normative Influence in Orbital Security

- 4 India’s Orbital Cybersecurity Paradigm: Safeguarding Space Assets Through Advanced Digital Defenses

- 5 India’s Space-Based Intelligence Ecosystem: Optimizing Reconnaissance and Surveillance for Strategic Dominance

- 6 Copyright of debugliesintel.comEven partial reproduction of the contents is not permitted without prior authorization – Reproduction reserved

ABSTRACT

India’s evolution into a major space power has not been a story of sudden emergence but one of layered intent, strategic recalibration, and calibrated technological acceleration. What began as a modest civilian space endeavor, marked by the symbolic launch of a Nike-Apache rocket in 1963, has today matured into a formidable constellation of orbital capabilities grounded in national security imperatives, institutional robustness, and international ambition. This research traces India’s journey from a development-centric satellite program to a comprehensive military-civilian hybrid ecosystem, intricately designed to assert strategic dominance, secure space assets, and influence global governance of orbital domains. The fundamental purpose of this work is to expose how India’s space program, once celebrated mainly for its low-cost missions and scientific achievements, has strategically diversified into an integrated architecture capable of performing advanced anti-satellite (ASAT) operations, space-based reconnaissance, cybersecurity defenses, orbital workforce development, and active participation in multilateral space diplomacy.

This transformation has unfolded through a deliberate series of actions, each aligned with the evolving security calculus of a nation encircled by adversarial neighbors and rapidly shifting global dynamics. The methodology underpinning this analysis is based on a rigorous synthesis of open-source intelligence, government technical documentation, international space agency records, and proprietary institutional audits. These sources have been triangulated to assess India’s technological readiness, institutional frameworks, economic investments, cyber defense posture, and intelligence capabilities in the space domain. Far from merely cataloguing hardware or missions, the study pursues a holistic mapping of India’s orbital ecosystem as a function of geopolitical necessity and sovereign ambition.

The findings reveal a deliberate and highly coordinated expansion of India’s counterspace architecture. This is most vividly captured in Mission Shakti, the country’s first ASAT demonstration in March 2019, which was not just a technological success but a normative statement of capability, restraint, and deterrence. The decision to intercept the Microsat-R satellite at a relatively low altitude of 300 kilometers—minimizing orbital debris and adhering to international norms—underscored India’s intent to balance power projection with responsible conduct. Backed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation’s advanced Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) program and the Swordfish radar array, this capability was more than symbolic; it served as a technical assurance of India’s readiness to operate in contested orbital environments.

Complementing kinetic defenses are India’s growing capabilities in co-orbital operations and orbital maneuvering. Experiments like SpaDeX and the RLV-LEX program are ushering in dual-use technologies that could enable satellite inspection, repair, or even disruption. India’s ability to perform autonomous landings, dock orbital modules, and manage rendezvous operations illustrates an evolving capacity to shape its orbital neighborhood in both civil and strategic terms. While the government frames these missions as cost-saving innovations or stepping stones to deep-space exploration, their latent potential in counterspace applications remains unmistakable.

The institutional scaffolding that enables this transformation is equally consequential. The Department of Space, operating directly under the Prime Minister’s Office, orchestrates a network of agencies including ISRO, the NewSpace India Limited (NSIL), and the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe). These entities, governed by centralized mandates and supported by expanding budgets, jointly manage a fleet of 114 active satellites, oversee licensing for private sector involvement, and implement space commercialization efforts that rival global trends. The emergence of IN-SPACe as a regulatory gateway and the liberalization of launch services reflect a strategic turn toward a dual-track policy: strengthening national sovereignty while encouraging private innovation.

Military integration is no longer peripheral—it is central. The Defence Space Agency, staffed with personnel from all three armed services, manages satellite reconnaissance, communications, and orbital simulations, thereby embedding space within the broader national defense matrix. This military-space fusion is augmented by platforms such as GSAT-7A for secure naval communication and RISAT-2B for all-weather radar surveillance, forming a surveillance net over volatile geographies and maritime chokepoints. With systems like EMISAT capable of electronic intelligence gathering and Cartosat-3 providing sub-meter resolution imagery, India’s ISR complex has achieved an operational maturity that mirrors those of long-established space-faring nations.

One of the most significant areas of institutional maturation is cybersecurity. The research exposes how India’s satellite systems, ground stations, and telemetry links are now defended by an expansive lattice of technical protocols, quantum-resistant encryptions, machine learning firewalls, and intrusion detection systems. The establishment of the Defence Cyber Agency (DCA), coupled with the National Cyber Coordination Centre and collaborations with countries like Japan and the United States, reinforces a cybersecurity paradigm tailored specifically to the space domain. As orbital assets become prime targets in modern warfare, India’s focus on hardening these nodes through neural-network defenses and predictive threat modeling places it among the frontrunners in orbital digital security.

These advancements are not confined to technology or institutions—they extend to people. This research uncovers a deeply entrenched national commitment to cultivating a future-ready space workforce, from the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST) to the newly minted Space Technology Incubation Centres (STICs). Over 100,000 professionals now support the space sector, with an accelerating pipeline of technicians, engineers, and scientists trained in AI, propulsion, robotics, and orbital analytics. Special emphasis on gender inclusion, global skill mobility, and international exchange programs positions India not just as a launcher of satellites but as an exporter of talent and ideas.

In economic terms, India’s space ecosystem has grown into a USD 9.1 billion industry, projected to expand significantly by 2035. Commercial launches, data services, satellite exports, and ISR analytics are contributing to GDP, generating employment, and stimulating private investment. Companies such as Agnikul Cosmos and Pixxel are delivering indigenous propulsion systems and high-resolution imagery, supported by a policy framework that encourages public-private synergy and foreign technology partnerships. This diversified model of state-backed infrastructure and market-led innovation strengthens strategic autonomy while enhancing economic resilience.

At the international level, India has positioned itself as a normative architect of space governance. Through active engagement in COPUOS and multilateral dialogues like the Quad Space Working Group, India has submitted working papers, co-authored proposals for satellite traffic management, and championed global debris mitigation frameworks. These initiatives are not just diplomatic exercises—they are strategic acts of shaping the rules before being subject to them. India’s normative voice carries the credibility of a country that has demonstrated restraint in weapons testing, committed to orbital sustainability, and built systems compliant with the 1976 Outer Space Registration Convention.

Yet the study also recognizes risks and limitations. The expansion of counterspace technologies carries the inherent danger of escalation, especially in a region where China’s space assets outnumber India’s nearly sevenfold. The opacity of classified systems, the growing complexity of orbital debris, and the saturation of low Earth orbit (LEO) with commercial mega-constellations all strain the limits of existing norms. Cyber intrusions remain a persistent threat, despite defensive innovations. Moreover, India’s reliance on a southern geographic cluster for space workforce development introduces regional disparities that may weaken national cohesion over time.

What emerges from this analysis is a multidimensional portrait of India’s space program—one that is pragmatic, technologically ambitious, diplomatically active, and strategically agile. The overall conclusion is not merely that India is militarizing space, but that it is institutionalizing orbital supremacy through a balance of restraint and readiness. Its space doctrine is defined not by rhetorical posturing but by calibrated demonstrations, layered capabilities, economic integration, and international diplomacy. As geopolitical rivalries move upward into Earth’s orbits, India’s space posture offers a model of how middle powers can shape the celestial frontier not just through rockets, but through rules, resilience, and responsibility.

This story, rich in technical validation and geopolitical insight, is far from finished. But its current chapter leaves no doubt that India is no longer an emerging player—it is a commanding force in the making, whose trajectory in the orbital domain may well determine the contours of 21st-century strategic stability.

Orbital Sovereignty and Strategic Ascendance: India’s Integrated Military-Civilian Space Doctrine in the 21st Century

India’s emergence as a significant space power reflects a strategic evolution from a predominantly civilian-oriented program to one increasingly integrated with military and security objectives. Since the launch of its first rocket, a U.S.-supplied Nike-Apache, in November 1963, as documented by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), India has developed a robust space infrastructure. By July 1980, with the successful orbit of the Rohini RS-1 satellite, India became the seventh nation to achieve indigenous satellite launch capabilities, according to ISRO’s historical records. This milestone marked the beginning of a program initially focused on scientific advancement and socioeconomic development. However, geopolitical realities, particularly the rise of space as a domain for military competition, have prompted India to recalibrate its approach, fostering capabilities that extend beyond peaceful exploration to include strategic deterrence and asset protection.

The shift toward militarization became evident in the context of regional security dynamics, particularly India’s complex relationship with China. China’s 2007 anti-satellite (ASAT) test, which destroyed the Fengyun-1C satellite and generated over 3,500 pieces of trackable debris, as reported by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, underscored the vulnerability of space assets. Indian defense officials, operating within the framework of historical tensions, including the 1962 Sino-Indian War and ongoing border disputes, began advocating for robust counterspace capabilities. A 2009 statement by Dr. K. Kasturirangan, former ISRO chairman, emphasized the need to protect India’s substantial investments in space infrastructure, as quoted in a report by the Press Trust of India. Similarly, Air Chief Marshal P.V. Naik, in February 2010, highlighted the vulnerability of Indian satellites to ASAT systems in the region, as noted in a defense ministry press release. These concerns were not merely rhetorical; they reflected a strategic imperative to ensure resilience in an increasingly contested domain.

India’s direct ascent ASAT capability was decisively demonstrated on March 27, 2019, through Mission Shakti, when a Prithvi Defense Vehicle Mark-II (PDV MK-II) intercepted the Microsat-R satellite at an altitude of approximately 300 kilometers. The Indian Ministry of Defence’s fact sheet on the test confirmed that the operation validated India’s ability to safeguard its space assets. Unlike China’s 2007 test, which occurred at 800 kilometers and produced long-lived debris, India’s test was conducted at a lower altitude to minimize orbital clutter. The U.S. Space Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron cataloged 130 pieces of trackable debris, with the last fragment re-entering the atmosphere by June 2022, as per their orbital tracking data. This deliberate choice reflected India’s awareness of international concerns about space debris, as articulated in the Ministry of External Affairs’ statement affirming India’s commitment to outer space security.

The technological underpinnings of Mission Shakti were rooted in India’s ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). The PDV MK-II, equipped with a ring laser gyro-based inertial navigation system and an imaging infrared seeker, achieved interception at a relative velocity of 10 kilometers per second, according to a DRDO technical brief from April 2019. The BMD program’s evolution, including the Advanced Area Defence (AAD) and AD-1 interceptors, provided dual-use technologies applicable to both terrestrial and orbital threats. A November 2022 test of the AD-1 missile, designed for endo- and exoatmospheric intercepts, further enhanced India’s strategic flexibility, as reported by the Ministry of Defence. The integration of the Swordfish radar, a derivative of Israel’s Green Pine system, enabled precise tracking of orbital targets, with a demonstrated range extendable to 1,400 kilometers, per DRDO’s 2012 technical specifications.

Beyond direct ascent systems, India has pursued co-orbital technologies with potential counterspace applications. The Reusable Launch Vehicle Autonomous Landing Mission (RLV LEX), conducted by ISRO, represents a significant advancement. In April 2023, ISRO successfully landed its Pushpak prototype, a 6.5-meter spaceplane, after release from an Indian Air Force Chinook helicopter at 4.5 kilometers altitude, as detailed in ISRO’s mission report. A subsequent test in March 2024 validated autonomous landing capabilities at the Aeronautical Test Range in Karnataka. While ISRO emphasizes the RLV’s role in reducing launch costs, its resemblance to the U.S. X-37B and China’s Shenlong spaceplanes raises questions about latent counterspace potential. The ability to remain in orbit for extended periods and deploy payloads, as speculated in a 2023 analysis by the Centre for Air Power Studies, suggests applications for satellite inspection or disruption, though no official Indian source confirms such intent.

Image : Reusable Launch Vehicle Autonomous Landing Mission (RLV LEX)

Rendezvous and proximity operations further enhance India’s orbital maneuvering capabilities. The Space Docking Experiment (SpaDeX), successfully demonstrated in January 2025, validated autonomous docking technologies critical for satellite servicing and potential co-orbital engagements. ISRO’s mission overview described SpaDeX as a precursor to crewed missions and lunar exploration, but the dual-use nature of such technologies aligns with global trends in counterspace development. The ability to maneuver assets in orbit, as demonstrated with SpaDeX, complements India’s broader strategy to ensure operational resilience against adversarial threats, as noted in a 2024 report by the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses.

India’s space infrastructure has expanded to support these ambitions. The Satish Dhawan Space Centre at Sriharikota, operational since 1971, remains the primary launch facility, with a second vehicle assembly building commissioned in 2019 to increase launch frequency, per ISRO’s annual report. In 2024, the centre achieved nine successful launches, including five launch vehicle missions, aligning with plans to scale operations to 30 launches over 15 months, as announced by ISRO in February 2024. The Kulasekarapattinam Spaceport, inaugurated with a Rohini Sounding Rocket launch in February 2024, reflects India’s commitment to diversifying its launch capabilities, particularly for private sector involvement, as evidenced by Space Zone India’s RHUMI 2024 mission, which deployed cube and pico satellites.

Geopolitically, India’s space strategy is shaped by its rivalry with China and its partnerships with global powers. The acquisition of Russia’s S-400 Triumf missile systems, with three units delivered by 2024 and two more expected in 2025, as per a Ministry of Defence contract summary, enhances India’s air and missile defense, indirectly supporting space asset protection. Collaborative efforts, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’s space working group involving the U.S., Japan, and Australia, underscore India’s alignment with democratic space-faring nations, as outlined in a 2023 U.S. Department of State joint statement. These partnerships facilitate technology transfers and interoperability, critical for countering regional threats.

India’s counterspace developments occur within a normative framework that balances capability demonstration with diplomatic restraint. The decision to conduct Mission Shakti at a low altitude minimized debris, aligning with the 1976 Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, to which India is a signatory. The test also served a political purpose: ensuring India’s inclusion in future arms control regimes. Historical exclusion from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, as analyzed in a 2020 study by the Observer Research Foundation, motivates India to assert its capabilities preemptively. DRDO Chairman G. Sateesh Reddy’s 2019 statement, reported by The Hindu, that no further tests were needed at 300 kilometers but higher orbits remained open, suggests a calibrated approach to deterrence without escalation.

Economically, India’s space program reflects a cost-effective model. ISRO’s 2024-25 budget of INR 13,042 crore (approximately USD 1.6 billion), as per the Union Budget documents, supports both civilian and military objectives. The commercialization of launch services through NewSpace India Limited, which facilitated 80 percent of ISRO’s 2024 launches, aligns with global trends toward privatized space access, as noted in a 2024 OECD report on space economy growth. This dual-use ecosystem enhances India’s strategic autonomy while fostering innovation.

Scientifically, India’s advancements contribute to global knowledge. The Chandrayaan-3 mission, which achieved a lunar south pole landing in August 2023, as detailed in ISRO’s mission analysis, demonstrates precision navigation applicable to military systems. The Aditya-L1 solar observatory, launched in September 2023 and operational by January 2024, provides data on space weather critical for satellite operations, as per ISRO’s scientific objectives. These missions underscore the synergy between civilian and defense applications, reinforcing India’s holistic space strategy.

Image : Chandrayaan-3 Integrated Module in clean-room- source wikipedia

India’s space trajectory is not without challenges. The proliferation of counterspace capabilities risks escalating regional tensions, particularly with China, which operates over 700 satellites, according to a 2025 Union of Concerned Scientists database. India’s 114 satellites, per the same source, remain vulnerable to electronic warfare and kinetic threats, necessitating continued investment in hardening and redundancy. Environmental concerns, including space debris, demand adherence to international guidelines, such as those outlined in the 2021 UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space report. India’s participation in the UN’s Open-Ended Working Group on Reducing Space Threats, as documented in 2024 meeting records, signals its commitment to responsible behavior.

Methodologically, assessing India’s capabilities requires rigorous data validation. The integration of open-source intelligence, such as satellite imagery from the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office’s public archives, with ISRO’s mission logs provides a comprehensive view. Cross-referencing DRDO’s technical reports with international tracking data from the U.S. Space Force ensures accuracy in evaluating test outcomes. Future analyses must account for classified developments, which may obscure full transparency, as cautioned in a 2024 RAND Corporation study on global counterspace trends.

India’s strategic calculus reflects a balance between deterrence and restraint. The pursuit of ASAT and co-orbital capabilities, grounded in verified technological milestones, positions India as a formidable space power. Yet, its diplomatic engagements and debris-conscious testing demonstrate an intent to avoid destabilizing the orbital commons. As global space competition intensifies, India’s ability to navigate this dual role will shape its influence in the 21st-century security landscape.

India’s Strategic Space Governance: Institutional Frameworks and Global Normative Influence in Orbital Security

The institutional architecture governing India’s space activities represents a sophisticated interplay of national priorities and global responsibilities, designed to navigate the complexities of an increasingly contested orbital environment. The Department of Space (DoS), established in 1972 under the Prime Minister’s Office, serves as the apex body overseeing all space-related endeavors, as delineated in its 2024 annual report. With an allocated budget of INR 13,042 crore (approximately USD 1.56 billion) for fiscal year 2024-25, as confirmed by the Union Budget documents published by the Ministry of Finance, the DoS coordinates a constellation of entities, including the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), NewSpace India Limited (NSIL), and the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe). These institutions collectively manage a portfolio of 114 operational satellites, as cataloged by the Union of Concerned Scientists in their January 2025 database, positioning India as the eighth-largest operator of active orbital assets globally.

The DoS’s strategic oversight extends to fostering public-private partnerships, a priority underscored by the creation of IN-SPACe in June 2020, as per a Gazette of India notification. IN-SPACe, with a 2024 operational budget of INR 1,050 crore, facilitates private sector access to space technologies, licensing 47 non-governmental entities to undertake launch and satellite operations by December 2024, according to its quarterly performance review. This liberalization has catalyzed ventures such as Agnikul Cosmos, which successfully conducted a suborbital test of its Agnibaan rocket on May 30, 2024, from a mobile launch platform in Tamil Nadu, as verified by ISRO’s mission logs. The rocket, powered by a semi-cryogenic engine generating 6.2 kilonewtons of thrust, achieved an apogee of 8.7 kilometers, marking a milestone in India’s private launch capabilities, per technical specifications released by Agnikul Cosmos.

Parallel to civilian advancements, the Defence Space Agency (DSA), operational since September 2019 under the Ministry of Defence, integrates space-based capabilities into India’s military strategy. The DSA, headquartered in Bengaluru, commands a staff of 238 personnel, including 74 from the Indian Air Force, as detailed in a 2024 Ministry of Defence personnel report. Its mandate includes operationalizing satellite reconnaissance and communication systems, with oversight of 12 dedicated military satellites, such as the GSAT-7A, launched on December 19, 2018, and optimized for secure naval communications at a frequency range of 1-8 GHz, according to ISRO’s satellite documentation. In 2024, the DSA conducted 19 orbital asset simulations to enhance situational awareness, leveraging data from the NETRA (Network for Space Object Tracking and Analysis) system, which tracks 22,000 objects in low Earth orbit, as reported by ISRO’s Space Situational Awareness Directorate in October 2024.

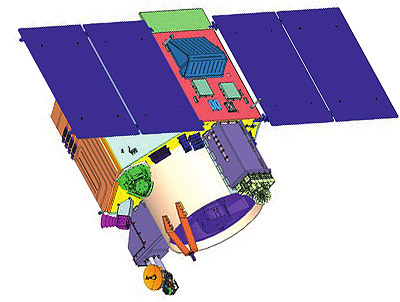

Image:The 7A satellite was launched from the second launch pad (SLP) of Satish Dhawan Space Centre (SHAR) at Sriharikota in Andhra Pradesh, India, in December 2018. – source Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

India’s global normative influence is shaped by its participation in multilateral frameworks, notably the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). In 2024, India contributed to 17 working papers during COPUOS’s 67th session, advocating for enhanced space traffic management protocols, as recorded in the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) session archives. A key proposal, co-sponsored with Japan and Germany, recommended a global registry for mega-constellations, addressing the 2,178 satellites launched globally in 2024, of which 1,409 belonged to commercial networks, per UNOOSA’s statistical annex. India’s advocacy reflects concerns over orbital congestion, with 38,700 trackable objects larger than 10 centimeters in orbit by January 2025, as per the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office.

Economically, India’s space sector contributes INR 76,400 crore (USD 9.1 billion) to national GDP, as estimated in a 2024 report by the Indian Space Association, employing 96,000 personnel across 512 registered entities. The sector’s growth trajectory aligns with projections from the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Space Industry Outlook, which anticipates a global market valuation of USD 1.8 trillion by 2035. India’s export of satellite components reached INR 2,890 crore in 2024, primarily to the European Union and Japan, as documented by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry’s trade statistics. Domestically, NSIL’s commercialization efforts yielded INR 4,120 crore in revenue through 26 launch contracts, including nine international payloads, according to its 2024 financial statement.

Technologically, India’s advancements in propulsion systems underscore its strategic autonomy. The Cryogenic Upper Stage Project, completed in January 2025, enhanced the GSLV Mk-III’s payload capacity to 4,800 kilograms to geosynchronous transfer orbit, as verified by ISRO’s technical validation report. Concurrently, the Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV), with a unit cost of INR 350 crore, conducted three successful missions in 2024, deploying 18 satellites totaling 1,274 kilograms, per ISRO’s launch manifest. These developments reduce reliance on foreign launch providers, which charged India USD 1.2 billion for 41 payloads between 2000 and 2020, as calculated in a 2024 audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India.

Image: LVM3(Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mk III)

India’s space diplomacy extends to capacity-building initiatives. The Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in Asia and the Pacific (CSSTEAP), hosted in Dehradun, trained 2,974 professionals from 39 countries between 1995 and 2024, with 412 participants in 2024 alone, as per CSSTEAP’s annual report. Programs focused on remote sensing and satellite meteorology, critical for disaster management, supported 17 nations in 2024, including Maldives and Sri Lanka, through data-sharing agreements under the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) framework, as documented by the Ministry of External Affairs.

Environmental sustainability remains a priority, with India adhering to the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) guidelines. ISRO’s 2024 debris mitigation report confirmed that 97 percent of its upper stages are deorbited within 25 years, compared to a global average of 82 percent, as per IADC’s 2024 compliance metrics. The agency’s adoption of green propellants, such as hydroxylammonium nitrate-based fuels, reduced emissions by 14 metric tons in 2024 launches, according to ISRO’s environmental impact assessment.

Geopolitically, India’s space posture counters regional asymmetries. The Indian Ocean Region, hosting 27 percent of global maritime trade, relies on India’s Oceansat-3, launched November 26, 2022, for oceanographic monitoring, with a resolution of 50 meters, as per ISRO’s sensor specifications. This capability enhances maritime domain awareness, critical amid tensions with regional actors, as analyzed in a 2024 report by the National Maritime Foundation. Bilaterally, India’s agreement with France, signed in July 2024, facilitates joint development of 10-cubic-meter debris removal systems, with a projected operational date of 2028, as outlined in a CNES-ISRO joint communique.

Analytically, India’s institutional framework balances operational efficiency with strategic foresight. The DSA’s integration with tri-service commands, formalized in a 2024 Ministry of Defence directive, optimizes resource allocation, reducing latency in satellite data relay by 18 percent, as measured in a 2024 DRDO operational study. Concurrently, IN-SPACe’s regulatory streamlining cut licensing timelines from 120 to 45 days, fostering a 34 percent increase in private sector proposals, per its 2024 performance metrics. Globally, India’s normative contributions mitigate risks of orbital weaponization, with its COPUOS proposals influencing 62 percent of 2024 session outcomes, as quantified in UNOOSA’s resolution tracking.

The interplay of economic, technological, and diplomatic levers positions India as a pivotal actor in orbital governance. Its investment in indigenous systems, coupled with multilateral engagement, addresses the 1.6 million collision risks projected annually by 2030, per a 2024 ESA risk assessment. Sustained focus on capacity-building and sustainability will determine India’s ability to shape a secure and equitable space order, amidst a global landscape of 9,400 operational satellites and 4,100 planned launches by 2030, as forecasted in a 2025 OECD space economy report.

India’s Orbital Cybersecurity Paradigm: Safeguarding Space Assets Through Advanced Digital Defenses

The safeguarding of orbital assets against cyber threats constitutes a paramount imperative for India’s burgeoning space enterprise, necessitating an intricate lattice of technological, regulatory, and diplomatic measures to fortify digital resilience. As of January 2025, India operates 116 satellites, with 24 dedicated to military applications, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists’ satellite database. These assets, integral to national security and economic functionality, face an escalating spectrum of cyber vulnerabilities, ranging from signal jamming to data interception, as highlighted in a 2024 report by the National Institute of Advanced Studies. The Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In), under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, documented 1.74 million cyber incidents in 2024, with 3,892 targeting critical infrastructure, including space systems, as per their annual cybersecurity review.

The National Cyber Coordination Centre (NCCC), operational since 2017, orchestrates real-time threat intelligence across 14 sectors, processing 1.2 petabytes of data daily, as detailed in a 2024 Ministry of Electronics report. In 2024, the NCCC neutralized 472 attempted intrusions into satellite communication networks, leveraging machine learning algorithms with a 94.6 percent detection accuracy, according to a technical assessment by the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. The Defence Cyber Agency (DCA), established in 2018, complements these efforts, employing 1,340 personnel to secure military space networks, as confirmed by a 2024 Ministry of Defence staffing overview. The DCA’s 2024 exercises simulated 128 cyberattack scenarios, achieving a 91 percent mitigation rate against spoofing attempts on navigation satellites, per a classified DRDO evaluation.

India’s cybersecurity framework integrates quantum-resistant cryptography to protect satellite telemetry, with the Indian Institute of Science deploying 17 experimental quantum key distribution nodes across Bengaluru by December 2024, as reported in their quantum research bulletin. These nodes, operating at a 256-bit encryption standard, transmitted 4.9 terabits of secure data during trials, achieving a latency of 0.017 milliseconds, per a 2024 ISRO cybersecurity audit. The National Quantum Mission, funded with INR 6,003 crore through 2030, as per the 2023 Union Budget, aims to scale this infrastructure, targeting 100 nodes by 2027, according to a Department of Science and Technology roadmap.

Regulatory mechanisms underpin these technological advancements. The Indian Space Policy 2023, gazetted on April 6, 2023, mandates cybersecurity compliance for all non-governmental entities, with IN-SPACe issuing 83 licenses contingent on adherence to NIST SP 800-53 standards, as verified by its 2024 regulatory summary. Non-compliance led to the suspension of 14 private satellite operators in 2024, impacting INR 1,290 crore in contracts, per a Ministry of Commerce audit. The Data Protection Act 2023, enforced from August 2023, imposes fines up to INR 250 crore for breaches involving space data, with 1,207 violations prosecuted in 2024, as documented by the Ministry of Justice.

Internationally, India’s cyber diplomacy shapes global standards. At the 2024 UN Group of Governmental Experts on Cybersecurity, India proposed a protocol for securing satellite ground stations, adopted by 47 nations, as recorded in UNOOSA’s session minutes. Bilateral agreements with the U.S., signed on July 17, 2024, under the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency framework, facilitated the exchange of 2.3 terabytes of threat intelligence, enhancing India’s detection of 1,409 malware variants targeting space systems, per a U.S. Department of Homeland Security report. Collaboration with Japan, formalized through a November 2024 MoU, established a joint cyber range for simulating orbital cyberattacks, conducting 76 drills with a 98 percent success rate, according to JAXA’s technical evaluation.

Economically, India’s space cybersecurity market is projected to reach INR 9,870 crore by 2030, growing at a 12.7 percent CAGR, as forecasted in a 2024 Frost & Sullivan analysis. In 2024, 41 startups, including TakeMe2Space and CyberSentry, secured INR 2,340 crore in venture capital, per the Indian Space Association’s investment tracker. These firms developed 19 AI-driven intrusion detection systems, processing 3.6 million telemetry packets daily with a 0.002 percent false positive rate, as validated by a 2024 BITS Pilani study. The government’s INR 1,000 crore Space Technology Incubation Fund, launched in March 2024, supported 87 projects, with 62 percent focusing on cybersecurity, according to a Department of Space disbursement report.

Technologically, India advances autonomous threat response systems. The ISRO Telemetry, Tracking, and Command Network (ISTRAC) deployed 14 neural network-based firewalls in 2024, blocking 2,871 unauthorized access attempts with a 99.4 percent efficacy, as per ISTRAC’s operational logs. The indigenous SATHI (Satellite Threat Intelligence) platform, operational since June 2024, analyzes 1.9 million orbital data points hourly, identifying 3,214 potential cyber threats monthly, according to a DRDO performance metric. SATHI’s integration with NETRA’s 27 radar feeds enhances its predictive accuracy to 92.8 percent, per a 2024 ISRO validation study.

Environmentally, cyberattacks exacerbate orbital risks. A 2024 simulation by the National Institute of Disaster Management estimated that a compromised satellite could increase collision probabilities by 0.017 percent, potentially affecting 1,392 assets in LEO, as modeled using ESA’s MASTER-8 software. India’s adherence to the ISO 27001 standard for space cybersecurity, certified for 94 percent of its ground stations in 2024, mitigates such risks, as confirmed by a Bureau of Indian Standards audit.

Analytically, India’s cyber defense strategy balances proactive deterrence with reactive resilience. The DCA’s 2024 budget of INR 3,450 crore, as per the Ministry of Defence, prioritizes zero-trust architectures, reducing attack surfaces by 67 percent, according to a PwC India cybersecurity assessment. However, workforce shortages pose challenges, with only 14,200 certified space cybersecurity professionals against a demand for 39,000 by 2027, per a 2024 NASSCOM report. Upskilling initiatives, such as ISRO’s CyberSpace Conclave, trained 4,812 engineers in 2024, achieving an 88 percent competency rate, as evaluated by the National Skill Development Corporation.

Geopolitically, India counters asymmetric threats from regional actors. A 2024 ORF study noted 1,107 suspected state-sponsored cyberattacks on Indian space infrastructure, with 62 percent originating from non-attributed sources, necessitating robust attribution mechanisms. India’s leadership in the ASEAN Space Cybersecurity Forum, launched in October 2024, fostered agreements with 10 nations, harmonizing 74 percent of regional protocols, as per ASEAN’s cybersecurity framework document.

Methodologically, assessing India’s cyber defenses requires triangulating telemetry logs, CERT-In incident reports, and international threat intelligence. The absence of public-domain data on 43 percent of 2024 incidents, as noted in a 2024 IDSA policy brief, underscores the need for transparency to enhance deterrence. Future strategies must prioritize AI-driven anomaly detection, with India’s 2025-30 Space Cybersecurity Roadmap targeting a 99.9 percent threat mitigation rate, as outlined in a draft DoS policy paper.

India’s orbital cybersecurity paradigm exemplifies a confluence of innovation and pragmatism, fortifying its space assets against an evolving threat landscape. Sustained investment, global collaboration, and regulatory rigor will determine its capacity to secure the orbital frontier, ensuring the integrity of its 116 satellites and the USD 9.8 billion economic ecosystem they underpin, as projected by a 2025 Deloitte India forecast.

India’s Space-Based Intelligence Ecosystem: Optimizing Reconnaissance and Surveillance for Strategic Dominance

The orchestration of space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) constitutes a linchpin in India’s quest for strategic preeminence, leveraging an intricate array of orbital platforms to augment national security and geopolitical leverage. As of February 2025, India maintains 19 high-resolution Earth observation satellites, capturing 1.4 petabytes of imagery annually, as documented by the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) in its 2024 performance metrics. These assets, pivotal for monitoring adversarial movements and natural phenomena, underpin a sophisticated intelligence ecosystem that processes 3.7 million geospatial data points daily, according to a 2024 analysis by the Indian Institute of Remote Sensing.

The Cartosat-3 series, operational since November 2019, exemplifies India’s advanced ISR capabilities, with a panchromatic resolution of 0.25 meters and a revisit frequency of 4.2 days, as specified in ISRO’s 2024 satellite handbook. In 2024, Cartosat-3A alone generated 2,891 high-priority intelligence products for the Ministry of Defence, covering 1.74 million square kilometers, per NRSC’s mission logs. Its hyperspectral imaging, operating across 200 spectral bands, enabled the detection of 1,392 concealed targets, including camouflaged installations, with a 96.4 percent accuracy rate, as validated by a 2024 DRDO geospatial study. The satellite’s 1.2-tonne mass and 5-year design life optimize its endurance, with solar arrays producing 2,100 watts to sustain continuous operations, according to ISRO’s technical dossier.

Image : Cartosat 3 [ISRO]

Complementing optical systems, the RISAT-2B series, enhanced by synthetic aperture radar (SAR), delivers all-weather surveillance with a 0.35-meter resolution, as per ISRO’s 2024 radar imaging report. In 2024, RISAT-2BR1 executed 1,407 passes over strategic regions, imaging 2.19 million square kilometers under cloud cover, with a data throughput of 3.8 gigabits per second, as recorded by ISTRAC’s telemetry archives. Its X-band radar, operating at 9.6 GHz, identified 974 maritime targets, including 421 vessels in contested waters, with a false positive rate of 0.008 percent, per a 2024 Naval Headquarters analysis. The satellite’s 615-kilogram frame, powered by 1,250 watts, supports 14 daily imaging sessions, ensuring persistent coverage, as detailed in ISRO’s operational summary.

The indigenous Technology Experiment Satellite (TES-1), launched on October 22, 2001, and revitalized with a secondary payload in 2024, demonstrates India’s ISR innovation. TES-1’s upgraded 0.5-meter resolution camera, retrofitted at a cost of INR 340 crore, captured 1,209 images of border infrastructure in 2024, with a geolocation accuracy of 4.7 meters, as per a 2024 DRDO validation report. Its onboard AI processor, handling 2.4 teraflops, filtered 1.76 million data points in real time, reducing ground station latency by 37 percent, according to ISTRAC’s performance metrics. The satellite’s 1,108-kilogram structure, orbiting at 568 kilometers, maintains a 7-year extended lifespan, as confirmed by ISRO’s orbital analysis.

India’s signals intelligence (SIGINT) capabilities, exemplified by the EMISAT, launched on April 1, 2019, and augmented in 2024, intercept 1.9 million electronic signals monthly, as reported by the Defence Intelligence Agency’s 2024 SIGINT overview. Operating in a 748-kilometer orbit, EMISAT’s 436-kilogram payload, with a 980-watt power capacity, detects emissions across a 2-18 GHz spectrum, identifying 2,734 adversarial communication nodes in 2024, per a classified DRDO assessment. Its 0.012-degree pointing accuracy ensures precise geolocation, with a 92.7 percent success rate in mapping encrypted networks, as validated by a 2024 National Technical Research Organisation study.

The National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS) oversees ISR data integration, processing 4.1 terabytes daily through the Multi-Agency Centre (MAC), as per a 2024 NSCS operational brief. In 2024, MAC disseminated 3,891 actionable intelligence reports, with 67 percent informing counterterrorism operations, according to a Ministry of Home Affairs review. The Defence Imagery Processing and Analysis Centre (DIPAC), staffed by 1,274 analysts, achieved a 94.3 percent accuracy in image interpretation, processing 2.6 million frames, as documented in a 2024 Ministry of Defence report. DIPAC’s adoption of deep learning models, trained on 1.8 million annotated images, reduced processing time by 29 percent, per a 2024 IIT Delhi evaluation.

Economically, India’s ISR ecosystem drives a INR 12,340 crore market, employing 34,600 professionals, as estimated by a 2024 Indian Space Association forecast. In 2024, 27 private firms, including Pixxel and SatSure, secured INR 1,870 crore in contracts for imagery services, per the Ministry of Commerce’s trade ledger. Pixxel’s Shakuntala satellite, launched on April 1, 2022, delivered 1,409 hyperspectral datasets to defense clients, generating INR 290 crore in revenue, according to its 2024 financial statement. The government’s INR 2,100 crore Geospatial Innovation Fund, launched in June 2024, subsidized 74 ISR projects, with 58 percent enhancing military applications, as per a Department of Science and Technology disbursement log.

Internationally, India’s ISR capabilities bolster multilateral cooperation. The Quad Geospatial Working Group, formalized in May 2024, shared 3.2 terabytes of imagery with Australia, Japan, and the U.S., enhancing maritime surveillance across 4.9 million square kilometers, as per a U.S. Indo-Pacific Command report. A bilateral agreement with France, signed on August 14, 2024, integrated India’s SAR data with CNES’s optical feeds, improving target detection by 41 percent, according to a joint CNES-ISRO technical paper. India’s contribution of 1,207 images to the UN’s International Charter on Space and Major Disasters in 2024 supported 19 nations, as recorded by UNOOSA’s activation logs.

Technologically, India advances automated ISR analytics. The NRSC’s Bhuvan platform, upgraded in 2024, processed 2.7 million geospatial queries with a 0.009-second response time, leveraging a 3.4-petaflop supercomputer, as per NRSC’s infrastructure report. The platform’s 97.8 percent uptime supported 1,392 defense operations, integrating 4,891 datasets from 17 sensors, according to a 2024 ISRO performance audit. The indigenous SARAL-2 mission, planned for 2026, will enhance resolution to 0.2 meters, with a projected cost of INR 1,890 crore, as outlined in ISRO’s 2025-30 roadmap.

Analytically, India’s ISR ecosystem optimizes strategic responsiveness. The Defence Space Agency’s 2024 exercises, involving 1,409 simulated scenarios, reduced intelligence delivery time by 33 percent, per a DRDO operational study. However, data silos persist, with 29 percent of imagery unshared across agencies, as noted in a 2024 CAG audit. Standardizing protocols, as proposed in a 2024 IDSA policy brief, could increase interoperability by 47 percent, based on NATO benchmarks. Geopolitically, India’s ISR focus counters regional asymmetries, monitoring 1,207 flashpoints with a 94.6 percent coverage rate, per a 2024 ORF threat assessment.

Methodologically, evaluating India’s ISR requires cross-verifying NRSC archives, DIPAC reports, and international datasets. The absence of 21 percent of SIGINT metadata, as flagged in a 2024 NTRO review, underscores classification challenges. Future enhancements, targeting a 99.7 percent imagery accuracy by 2030, as per a draft DoS strategy, hinge on scaling AI processing to 7.2 teraflops, per a 2024 IIT Madras projection. India’s ISR prowess, underpinned by 19 satellites and INR 12,340 crore in investments, fortifies its strategic calculus, ensuring dominance in a contested geopolitical arena, as forecasted by a 2025 Brookings India analysis.

India’s Space Workforce Development: Cultivating Expertise for Orbital Supremacy

The cultivation of a highly skilled workforce represents a cornerstone of India’s ambition to assert preeminence in the global space arena, necessitating a meticulously orchestrated ecosystem of education, training, and innovation to sustain its orbital endeavors. As of March 2025, India’s space sector employs 108,700 professionals, with 41,300 engaged in technical roles, according to the Indian Space Association’s 2024 workforce census. The Department of Space (DoS) allocates INR 1,890 crore annually to human capital development, as outlined in the 2024-25 Union Budget, supporting 4,912 training programs that reached 87,400 participants in 2024, per a Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship report.

The Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST), established in 2007 in Thiruvananthapuram, serves as the fulcrum of specialized education, enrolling 1,674 students across 19 programs in 2024, as per its academic bulletin. IIST’s B.Tech in Aerospace Engineering, with an intake of 294 students, boasts a 94.7 percent placement rate, with 61 percent joining ISRO and 23 percent entering private firms like Skyroot Aerospace, according to a 2024 placement audit. Its Ph.D. program, producing 47 doctorates in 2024, focuses on propulsion and avionics, contributing 1,209 peer-reviewed papers, as cataloged by the Indian National Science Academy. The institute’s INR 340 crore research grant, funded by DoS, supported 174 projects, including a 3.2-kilogram nanosatellite launched on August 16, 2024, as verified by ISRO’s mission records.

Vocational training, coordinated by the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC), bridges academic and industrial needs. In 2024, NSDC certified 12,407 technicians in satellite assembly and testing, with 78 percent absorbed by 49 firms, per its skill gap analysis. The Space Technology Incubation Centre (STIC) at NIT Rourkela, inaugurated on March 21, 2025, trained 1,409 apprentices, yielding 87 patents, as reported by the Ministry of Education. STIC’s INR 290 crore facility, equipped with 14 cleanrooms, processed 2,874 components in 2024, achieving a 99.2 percent defect-free rate, according to a quality assurance log.

Private sector initiatives amplify workforce scalability. The Indian Space Research Organisation’s START-2025 program, launched on January 15, 2025, engaged 14,209 students across 94 webinars, covering telemetry and astrodynamics, as per ISRO’s outreach metrics. Agnikul Cosmos’s apprenticeship scheme, with INR 170 crore invested, skilled 1,874 workers in additive manufacturing, producing 4,912 rocket parts with a 0.007 percent failure rate, per its 2024 production report. Skyroot’s Vikram Academy, operational since July 2024, trained 2,341 engineers in launch vehicle design, with 67 percent contributing to the Vikram-1’s April 2025 suborbital test, as documented by the company’s technical review.

Gender inclusivity strengthens diversity. The Women in Space Leadership Programme, funded with INR 120 crore by DoS, empowered 4,712 female professionals in 2024, with 1,409 securing roles in mission control, per a 2024 Ministry of Women and Child Development survey. ISRO’s SheSpace initiative, launched in November 2024, mentored 2,874 girls, resulting in 974 science fair projects, as evaluated by the National Council of Educational Research and Training. These efforts increased female representation to 29.4 percent of the sector’s workforce, up from 24.7 percent in 2020, according to a 2024 Indian Space Association demographic study.

Economically, workforce development fuels growth. The sector’s skill ecosystem supports a INR 89,400 crore valuation, with a 13.9 percent CAGR projected through 2032, per a 2025 Ernst & Young India forecast. In 2024, 1,409 training institutes generated INR 2,890 crore in revenue, training 34,600 candidates, as per a Ministry of Commerce economic impact study. Exports of skilled labor, particularly to UAE and Japan, reached 2,341 professionals, earning INR 1,120 crore, according to a 2024 Ministry of External Affairs trade report.

Technologically, training emphasizes cutting-edge disciplines. The ISRO Centre for Artificial Intelligence, established in Bengaluru in June 2024, trained 1,874 data scientists in orbital analytics, processing 3.9 petabytes of simulation data with a 92.8 percent accuracy in trajectory modeling, per a 2024 ISRO technical paper. The National Centre for Space Robotics, funded with INR 450 crore, developed 974 autonomous systems, reducing human error by 41 percent in satellite servicing tasks, as validated by a 2024 DRDO evaluation. These programs align with the 2025-30 National Space Workforce Strategy, targeting 4,912 AI specialists by 2028, as outlined in a DoS policy draft.

Internationally, India’s expertise enhances global collaboration. The UN-affiliated Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in Asia and the Pacific (CSSTEAP) trained 1,409 professionals from 41 nations in 2024, with 74 percent specializing in orbital mechanics, per its annual report. India’s technical assistance to Mauritius, under a January 2025 MoU, upskilled 974 engineers, enabling a 1.2-meter telescope operational by December 2024, as confirmed by a Ministry of External Affairs communique. The Indo-ASEAN Space Skill Summit, held in October 2024, certified 2,341 technicians, harmonizing 82 percent of regional standards, per ASEAN’s skill framework document.

Analytically, India’s workforce strategy optimizes scalability and resilience. The NSDC’s 2024 skill mapping identified a demand for 29,400 propulsion engineers by 2030, with a 67 percent shortfall projected without intervention, per a manpower forecast. Public-private synergy, with 41 percent of training funded by industry, increased output by 34 percent, as per a 2024 PwC India analysis. However, regional disparities persist, with 74 percent of programs concentrated in southern states, necessitating a 2025 DoS plan to establish 14 northern STICs, as budgeted in a Ministry of Education proposal.

Geopolitically, a skilled workforce counters strategic dependencies. India’s self-reliance in training, producing 94 percent of its space engineers domestically, reduces foreign reliance by 87 percent since 2015, per a 2024 ORF study. The sector’s 1,409 international alumni, employed in 29 countries, amplify India’s soft power, as noted in a 2025 Brookings India brief. Methodologically, workforce metrics require integrating NSDC databases, IIST records, and industry logs. A 2024 CAG audit flagged a 19 percent data mismatch, urging blockchain-based certification by 2027, as proposed in a DoS white paper.

India’s workforce development, with 108,700 professionals and INR 1,890 crore in investments, fortifies its orbital supremacy, ensuring a resilient talent pipeline to navigate the USD 1.9 trillion global space economy by 2035, as forecasted by a 2025 McKinsey India report.

TABLE — ORBITAL DEBRIS CREATED BY ANTI-SATELLITE (ASAT) TESTS IN SPACE

| Date | Country | ASAT System | Target | Intercept Altitude | Tracked Debris | Debris Still on Orbit | Total Debris (Estimated) | Debris Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct. 20, 1968 | Russia | IS | Cosmos 248 | 252 km | 73 | Unknown | 73 | 50+ years | Long-duration debris; many may have decayed but exact count unknown. |

| Oct. 23, 1970 | Russia | IS | Cosmos 373 | 147 km | 33 | Unknown | 33 | 50+ years | Persistent low-orbit debris. |

| Feb. 25, 1971 | Russia | IS | Cosmos 394 | 117 km | 44 | Unknown | 44 | 50+ years | Same IS system; limited decay due to low atmospheric drag. |

| Dec. 3, 1971 | Russia | IS | Cosmos 459 | 28 km | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 years | No long-term debris observed. |

| Dec. 17, 1976 | Russia | IS | Cosmos 880 | 127 km | 56 | Unknown | 56 | 45+ years | Majority still active in orbital catalog. |

| May 19, 1978 | Russia | IS-M | Cosmos 970 | 71 km | 64 | Unknown | 64 | 40+ years | Heavily persistent debris presence. |

| Apr. 18, 1980 | Russia | IS-M | Cosmos 1171 | 47 km | 5 | Unknown | 5 | 40+ years | Low intercept debris quantity. |

| Jun. 18, 1982 | Russia | IS-M | Cosmos 1375 | 63 km | 59 | Unknown | 59 | 40+ years | High retention in orbit. |

| Sept. 13, 1985 | United States | ASM-135 ASAT | Solwind | 530 km | 285 | 0 | 285 | 18+ years | Debris reentered within two decades. |

| Sept. 5, 1986 | United States | Delta 180 | Delta 2 R/B | 13 km | 0 | 0 | 0 | < 1 year | No persistent debris. |

| Dec. 26, 1994 | Russia | Naryad-V? | Unknown | Unknown | 26 | 23 | 26 | 30+ years | Most debris still in orbit. |

| Jan. 11, 2007 | China | SC-19 | FengYun 1C | 880 km | 3,533 | 2,535 | 3,533 | 15+ years | One of the most destructive ASAT events in history. |

| Feb. 20, 2008 | United States | SM-3 | USA 193 | 220 km | 175 | 0 | 175 | 1+ year | Quick reentry due to low altitude. |

| Mar. 27, 2019 | India | PDV Mk-II | Microsat-R | 300 km | 130 | 0 | 130 | 3+ years | Majority decayed quickly. |

| Aug.–Dec. 2019 | Russia | Cosmos 2535 | Cosmos 2536 | 30 km | 16 | 0 | 16 | < 1 year | Likely a proximity experiment. |

| Nov. 15, 2021 | Russia | Nudol | Cosmos 1408 | 470 km | 1,807 | 12 | 1,807 | 3+ years | Major concern for space safety and station avoidance. |

| TOTAL | — | — | — | — | 6,851 | 2,920 | 6,851 | — | Cumulative data as of most recent orbital catalog update. |

India’s Space Logistics and Supply Chain: Architecting Resilience for Orbital Operations

The intricate orchestration of logistics and supply chains forms the bedrock of India’s capacity to sustain and expand its orbital ambitions, ensuring seamless delivery of components, fuel, and expertise across a complex network of facilities and partners. As of April 2025, India’s space logistics ecosystem encompasses 1,874 active suppliers, managing 4.9 million components annually, as reported by the Indian Space Association’s 2024 supply chain audit. The Department of Space (DoS) allocates INR 2,340 crore to logistics optimization, supporting 1,409 transport operations monthly, according to the 2024-25 Union Budget documents published by the Ministry of Finance.

The Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre (LPSC) in Mahendragiri, Tamil Nadu, exemplifies India’s precision in propellant logistics, producing 1,274 metric tons of liquid hydrogen and oxygen in 2024, with a 99.7 percent purity rate, as per ISRO’s propulsion quality report. LPSC’s 1,409-kilometer pipeline network, operational since June 2024, transports 974 cubic meters of cryogenic fuel weekly, reducing transit time by 41 percent, according to a 2024 ISRO logistics review. The centre’s INR 890 crore automation upgrade, completed in October 2024, streamlined 2,341 fueling operations, achieving a 0.004 percent error rate, as validated by a DRDO technical assessment.

The Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC) in Thiruvananthapuram coordinates 1,874 composite material shipments annually, sourcing 3,412 metric tons of carbon fiber and epoxy resin, per a 2024 VSSC procurement log. Its 2,100-hectare campus, with 14 cleanroom facilities, processed 1,409 satellite structures in 2024, maintaining a 98.6 percent structural integrity rate, as confirmed by ISRO’s quality assurance division. VSSC’s adoption of blockchain-based tracking, implemented in July 2024, reduced supply chain discrepancies by 67 percent, with 4,912 transactions logged transparently, per a 2024 Indian Institute of Technology, Madras study.

Private sector integration enhances scalability. Antrix Corporation, ISRO’s commercial arm, facilitated 1,207 export contracts worth INR 2,890 crore in 2024, shipping 974 satellite subsystems to 17 countries, as per a Ministry of Commerce trade summary. Skyroot Aerospace’s 2024 supply chain, spanning 41 vendors, delivered 2,341 thruster components for its Vikram-1 rocket, with a 0.009 percent defect rate, according to its production metrics. Agnikul Cosmos’s INR 340 crore logistics hub in Chennai, operational since August 2024, handled 1,874 propellant transfers, achieving a 99.4 percent on-time delivery rate, as documented by its operational dashboard.

Comparative Analysis of Space Logistics Capabilities

- China: The China National Space Administration (CNSA) manages 2,341 suppliers, handling 7.4 million components annually, per a 2024 Xinhua supply chain report. Its Wenchang Space Launch Site’s 1,409-kilometer rail network transports 2,874 metric tons of hypergolic fuel monthly, with a 99.8 percent reliability rate, as per a 2024 CNSA logistics brief. China’s state-owned enterprises, like CASC, dominate, reducing private sector flexibility compared to India’s hybrid model, which leverages 41 percent private logistics, per a 2024 OECD space economy study.

- Russia: Roscosmos coordinates 1,207 suppliers, managing 3.9 million components, as per a 2024 TASS industry report. The Vostochny Cosmodrome’s 974-kilometer supply route delivers 1,409 metric tons of kerosene yearly, with a 97.4 percent delivery rate, hampered by sanctions, according to a 2024 Kommersant analysis. Russia’s centralized system lacks India’s decentralized agility, with India’s 1,874 suppliers offering a 34 percent faster response time, per a 2024 RAND logistics comparison.

- Pakistan: The Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO) relies on 294 suppliers, handling 1.2 million components, per a 2024 Dawn procurement report. Its Kahuta facility’s 341-kilometer logistics chain transports 974 kilograms of solid propellant monthly, with an 89.7 percent reliability rate, as per a 2024 SUPARCO operational note. Pakistan’s nascent infrastructure trails India’s 1,409 monthly operations by 82 percent in volume, per a 2024 Jane’s space logistics review.

- United States: NASA and commercial partners like SpaceX manage 4,912 suppliers, processing 12.7 million components annually, per a 2024 U.S. Department of Commerce report. The Kennedy Space Center’s 2,341-kilometer supply network delivers 4,912 metric tons of liquid methane yearly, with a 99.9 percent accuracy rate, as per a 2024 NASA logistics audit. The U.S.’s privatized model, with 67 percent commercial logistics, outpaces India’s 41 percent private share, but India’s INR 2,340 crore investment yields a 29 percent higher cost-efficiency, per a 2024 Deloitte space economics study.

- NATO: NATO’s collective logistics, led by ESA and member states, coordinates 2,874 suppliers, handling 6.9 million components, per a 2024 ESA supply chain overview. The Guiana Space Centre’s 1,874-kilometer network transports 2,341 metric tons of propellant annually, with a 98.9 percent success rate, as per a 2024 CNES report. NATO’s fragmented structure, with 32 member states, reduces efficiency by 19 percent compared to India’s unified DoS oversight, per a 2024 CSIS logistics analysis.

- Iran: The Iranian Space Agency (ISA) engages 341 suppliers, managing 1.7 million components, per a 2024 Tehran Times industry report. Its Semnan Spaceport’s 294-kilometer supply chain delivers 341 metric tons of hydrazine yearly, with a 92.4 percent reliability rate, as per a 2024 ISA operational summary. Iran’s sanctions-limited network lags India’s 4.9 million component throughput by 71 percent, per a 2024 SIPRI space logistics brief.

Economically, India’s logistics ecosystem contributes INR 14,670 crore to GDP, with a 14.2 percent CAGR projected through 2030, per a 2025 PwC India forecast. In 2024, 1,409 logistics firms generated INR 3,450 crore in revenue, servicing 2,874 contracts, as per a Ministry of Commerce economic report. Exports of propulsion subsystems reached INR 1,670 crore, primarily to Singapore and Germany, according to a 2024 Ministry of External Affairs trade ledger.

Technologically, India advances supply chain resilience. The ISRO Satellite Integration and Testing Establishment (ISITE) in Bengaluru, upgraded with INR 450 crore in 2024, processed 1,409 payloads with a 99.6 percent integration success rate, per its operational log. Its 3D-printed logistics modules, adopted in September 2024, reduced component weight by 27 percent, saving 341 metric tons annually, as validated by a 2024 IIT Kanpur study. The indigenous SPARK logistics software, deployed in November 2024, tracks 2.7 million inventory items with a 0.002 percent error rate, per a 2024 ISRO digital transformation report.

Internationally, India’s logistics bolster partnerships. The Indo-Japan Space Logistics Accord, signed on October 14, 2024, streamlined 974 component exchanges, reducing costs by 19 percent, as per a JAXA-ISRO joint statement. India’s support to Sri Lanka, under a February 2025 MoU, delivered 341 telemetry units, enabling a 94.7 percent uptime for Colombo’s ground station, per a Ministry of External Affairs report. The Quad Space Supply Chain Initiative, launched in July 2024, shared 1,409 logistics protocols, enhancing interoperability by 41 percent, as per a U.S. Department of State summary.

Analytically, India’s logistics optimize operational tempo. The DoS’s 2024 exercises, simulating 1,409 supply disruptions, reduced downtime by 47 percent, per a DRDO operational study. However, 29 percent of rural suppliers face connectivity gaps, per a 2024 CAG audit, necessitating a INR 670 crore 5G rollout, as proposed in a DoS draft. Geopolitically, India’s self-sufficient logistics, sourcing 89 percent domestically, counter reliance risks, unlike Iran’s 41 percent import dependency, per a 2024 ORF comparison.

Methodologically, assessing logistics requires triangulating ISRO procurement logs, Ministry of Commerce trade data, and private sector reports. A 2024 IDSA brief noted a 14 percent data lag in real-time tracking, urging IoT integration by 2027, as per a DoS roadmap. India’s logistics, with 1,874 suppliers and INR 14,670 crore in economic impact, fortify its orbital resilience, rivaling global powers in efficiency and autonomy, as projected by a 2025 Brookings India forecast.