Contents

- 0.1 ABSTRACT

- 0.2 NATO and the European Funding of US Military Support for Ukraine: A Complex Nexus in the Geopolitical Landscape

- 0.3 Reinforcing Strategic Autonomy: The Path Towards European Defense Integration

- 0.4 Strategic Adaptation and the Shifting Paradigm of U.S. Influence in NATO

- 0.5 Decoding Russia’s Strategic Calculations and Geopolitical Maneuvering in the Ukraine Conflict

- 0.6 Recalibrating the Global Order: Strategic Realignments and Emerging Security Paradigms

- 0.7 The Strategic Balance of Economic Pressure and Diplomatic Engagement in Geopolitical Conflict

- 0.7.1 The Fragility of Russia’s Economic Framework Under Heightened Sanctions

- 0.7.2 Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Economic Contagion Risks

- 0.7.3 Diplomatic Leverage Through Economic Measures: Opportunities and Challenges

- 0.7.4 Repercussions for U.S. Domestic and Foreign Policy

- 0.7.5 Strategic Considerations for NATO’s Collective Response

- 0.7.6 The Path Forward: Balancing Economic Pressure and Diplomatic \Engagement

- 0.7.7 Impact on Russia’s Energy Sector

- 0.7.8 Financial Repercussions on Global Trade and Supply Chains

- 0.8 Quantitative Analysis of U.S. Sanctions and Financial Isolation

- 0.9 The Kremlin’s Geopolitical Calculus Under Economic Strain

- 0.10 Enhancing Multilateral Collaboration for Sustainable Peace

- 0.11 The Case for International Peacekeeping Forces

- 0.12 Comprehensive Analysis of the Economic Transformation Triggered by NATO’s 5% Defense Mandate

- 0.13 What would happen if the US also increased its NATO membership to 5%?

- 0.14 Disaggregating the Economic Impact Across All NATO States (Corrected Analysis Based on Official Data)

- 0.15 In-depth analysis – Analyzing the Economic and Strategic Impact of the 5% Defense Spending Mandate on NATO Member States

- 0.15.1 Germany: A Deep Dive into Fiscal and Strategic Implications

- 0.15.2 France: Economic Expansion and Strategic Recalibration

- 0.15.3 United Kingdom: Unprecedented Fiscal Demands and Societal Adjustments

- 0.15.4 Italy: Navigating Debt Constraints and Strategic Priorities

- 0.15.5 Canada: Strengthening Arctic Security and NATO Contributions Amid Budgetary Strains

- 0.15.6 Spain: Fiscal and Societal Transformations Amid Military Expansion

- 0.15.7 Poland: Bolstering Eastern Border Security and Strategic Investments

- 0.15.8 Netherlands: Expanding Cybersecurity and NATO Collaboration

- 0.15.9 Norway: Strategic Overperformance and Arctic Leadership

- 0.15.10 Turkey: Strengthening NATO’s Southern Flank Amid Regional Challenges

- 0.15.11 Sweden: Strengthening Baltic Defense and Advancing Technological Leadership

- 0.15.12 Denmark: Expanding Naval and Air Defense Capabilities

- 0.15.13 Greece: Sustaining High Contributions and Enhancing Regional Stability

- 0.15.14 Portugal: Emphasizing Naval Expansion and Atlantic Security

- 0.15.15 Romania: Strengthening Black Sea Defenses and Modernizing Military Infrastructure

- 0.15.16 Finland: Countering Russian Aggression with Strategic Investments

- 0.15.17 Belgium: Reallocating Finances to Meet NATO’s 5% Defense Spending Mandate

- 0.15.18 Czech Republic: Doubling Defense Spending for NATO Operations

- 0.15.19 Hungary: Escalating Defense Investments to Secure Border Security and NATO Commitments

- 0.15.20 Slovakia: Doubling Defense Spending to Strengthen NATO Interoperability

- 0.15.21 Bulgaria: Strategic Modernization and NATO Integration Amid Increased Defense Spending

- 0.15.22 Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Bolstering Baltic Security Through Comprehensive Defense Expansion

- 0.15.23 Croatia: Expanding Naval and Air Capabilities Amid Economic Challenges

- 0.15.24 Slovenia: Transforming Defense Capabilities Amid Fiscal Constraints

- 0.15.25 Luxembourg: Strategic Investment in Defense Amidst Economic Strength

- 0.15.26 Iceland: Enhancing Arctic Security Amid Limited Resources

- 0.15.27 Albania: Economic Strains and Strategic Aspirations in Meeting NATO Mandates

- 0.15.28 Montenegro: Scaling Up Defense Amidst Limited Resources

- 0.15.29 North Macedonia: Balancing External Support and Domestic Priorities

- 0.16 Macroeconomic Ramifications and Strategic Considerations

- 0.16.1 Economic Reallocation and Fiscal Constraints

- 0.16.2 Inflationary and Macroeconomic Pressures

- 0.16.3 Technological Advancements and Economic Opportunities

- 0.16.4 Strategic Implications for Collective Defense

- 0.16.5 Burden-Sharing and Alliance Cohesion

- 0.16.6 Societal and Political Challenges

- 0.16.7 Recommendations for Sustainable Implementation

- 0.17 Table 1 : Defence expenditure

- 0.18 Table 3 : Defence expenditure as a share of GDP and annual real change

- 0.19 Table 6 : GDP per capita and defence expenditure per capita

- 0.20 Table 7 : Military personnel

- 0.21 Table 8a : Distribution of defence expenditure by main category

- 0.22 Table 8b : Distribution of defence expenditure by main category

- 1 NATO defence expenditure

ABSTRACT

The insights shared by Mark Rutte during the World Economic Forum have emerged as a turning point for NATO’s evolution, hinting at profound changes in how transatlantic security responsibilities will be distributed in the years to come. His candid observations about European taxpayers potentially financing U.S. military supplies to Ukraine do not merely reflect an isolated financial concern but rather capture the essence of a broader rethinking of roles, obligations, and the very foundation of collective defense. This issue is not just about Ukraine or military logistics—it speaks to the heart of how NATO as an alliance can adapt to shifting global dynamics and its own internal tensions. The importance of this lies in the delicate balance NATO must strike between maintaining unity and evolving into a structure that equally prioritizes both collective and national interests.

NATO’s transformation, as highlighted by Rutte, cannot be fully understood without acknowledging its historical dependence on the United States. This reliance, which was instrumental in creating a secure post-World War II Europe, has now exposed vulnerabilities as Europe confronts systemic issues in its defense capabilities. For decades, Europe has relied heavily on American support, benefiting from an asymmetry of military and financial power that allowed European nations to prioritize domestic growth while the United States bore the lion’s share of NATO’s operational costs. While this arrangement fostered unparalleled collaboration, it also delayed Europe’s ability to establish its own autonomous defense infrastructure. Now, with global adversaries becoming increasingly unpredictable and U.S. domestic politics signaling possible shifts in transatlantic engagement, the alliance faces a pivotal question: how can it achieve equitable burden-sharing without fracturing under the weight of these adjustments?

Rutte’s emphasis on burden-sharing cuts to the core of NATO’s sustainability. The issue of fair contribution is not new but has become more pressing against the backdrop of economic instability across Europe. With inflation surging, energy prices escalating, and GDP growth stagnating, many member states find themselves caught between competing priorities. Smaller economies, such as Latvia and Bulgaria, face the toughest trade-offs, with limited fiscal space to increase defense spending without sacrificing critical public investments. Wealthier nations like Germany and France have greater capacity, but their willingness to shoulder additional financial responsibilities is tempered by domestic political resistance and competing social priorities. The situation demands creative financial mechanisms that redistribute the economic strain more equitably, such as centralized funding models or pooled procurement initiatives. Without such strategies, NATO risks exacerbating inequalities within the alliance, ultimately undermining its operational effectiveness and cohesion.

The challenges of financial realignment are compounded by inefficiencies in Europe’s defense procurement and production systems. Rutte’s remarks bring into sharp focus the fragmented state of European military industries, which remain hamstrung by national silos and lack the cohesion needed to independently sustain high-intensity operations. Despite efforts to standardize equipment and streamline production, European nations often pursue divergent priorities, duplicating efforts and diluting potential gains in efficiency. Overcoming these barriers will require not only investment in integrated defense strategies but also the political will to prioritize collective over national interests. This is no small task, as it involves reshaping entrenched procurement practices and fostering unprecedented collaboration among European states, many of which remain hesitant to cede sovereignty over defense matters.

At the same time, Europe’s dependency on U.S. military-industrial support cannot be ignored. Decoupling from American supply chains will not happen overnight, nor can it be achieved without a clear vision and significant investment in domestic capabilities. From advanced surveillance systems to missile defense platforms, the technological edge that the United States provides remains critical to NATO’s operational readiness. Nonetheless, Rutte’s call for a rebalancing of responsibilities is a timely reminder that Europe must take meaningful steps toward reducing this dependency. Establishing collaborative research hubs, increasing funding for defense innovation, and incentivizing joint procurement agreements are some of the pathways through which Europe can build a more self-reliant defense posture.

Beyond logistics and finances, the broader geopolitical implications of Rutte’s remarks deserve careful attention. His statements resonate with growing concerns about the potential for reduced U.S. involvement in European security, a scenario that has become increasingly plausible given Washington’s focus on other global theaters, particularly the Indo-Pacific. This reality forces Europe to reconsider its role not just within NATO but as a global security actor. The paradox is clear: while Europe must invest more heavily in defense, public opinion across the continent remains largely resistant to such measures. In many countries, citizens are grappling with economic hardships, and calls for increased military spending often clash with demands for improved social services and infrastructure. This tension presents a formidable challenge for European leaders, who must find ways to reconcile these competing priorities while maintaining public support.

Rutte’s vision also underscores the strategic necessity of modernizing Europe’s approach to defense innovation. Technological advancements in artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and autonomous systems are redefining the landscape of global security, and NATO’s ability to remain competitive hinges on its capacity to harness these technologies effectively. Europe, in particular, faces an urgent need to close the innovation gap with adversaries such as Russia and China. By pooling resources and expertise, European nations can not only achieve cost efficiencies but also ensure that their defense capabilities are future-proofed against emerging threats. However, this will require significant investments in research and development, as well as the creation of frameworks that facilitate cross-border collaboration in sensitive technological domains.

Rutte’s statements are also a powerful commentary on NATO’s internal identity and external influence. The alliance must navigate a delicate balance between reinforcing its collective defense commitments and addressing the diverging priorities of its member states. This includes grappling with existential questions about its long-term relevance in a world where traditional security paradigms are increasingly challenged by hybrid threats, cyberattacks, and climate-induced instability. Furthermore, NATO’s recalibration has global ramifications. Its evolving posture sends a strong signal to adversaries that the alliance is capable of adapting to new challenges, but it also risks fueling an arms race that could further destabilize global security dynamics.

Ultimately, Rutte’s insights compel us to confront the broader implications of NATO’s transformation. This is not merely a story of budgets or weaponry; it is a narrative about the resilience and adaptability of an alliance that has been the cornerstone of transatlantic security for over seven decades. The challenges are immense, but so too are the opportunities to redefine NATO’s role in a rapidly changing world. By embracing innovation, fostering equitable burden-sharing, and prioritizing unity, NATO can navigate this critical juncture and emerge as a stronger, more cohesive force for global stability. The stakes are high, but the path forward is clear: the alliance must evolve, not just to meet the demands of today but to anticipate and address the uncertainties of tomorrow.

NATO and the European Funding of US Military Support for Ukraine: A Complex Nexus in the Geopolitical Landscape

Mark Rutte’s insights at the World Economic Forum signal a watershed moment in NATO’s trajectory. His assertion that European taxpayers may soon shoulder the cost of U.S. military supplies to Ukraine is emblematic of a broader redefinition of transatlantic responsibilities. To fully comprehend the underpinnings of such a shift, it is critical to explore the deep-seated economic structures, defense dependencies, and strategic recalibrations that define this unprecedented geopolitical transformation.

The recalibration of financial and logistical commitments among NATO members is not merely a response to the immediate exigencies of the Ukraine conflict. Instead, it is part of a larger pattern driven by systemic vulnerabilities in Europe’s defense capabilities, the mounting unpredictability of global adversaries, and the necessity of a unified yet equitable alliance. Historically, NATO’s foundation has been underpinned by an asymmetry of power, with the United States absorbing the lion’s share of expenditures and operational responsibilities. This dependency, while fostering unparalleled transatlantic cooperation, has perpetuated inefficiencies in Europe’s autonomous defense readiness.

Rutte’s emphasis on burden-sharing extends far beyond the rhetorical. The evolving nature of NATO’s obligations demands an integrative approach to financing, wherein the realignment of defense contributions addresses disparities not only between Europe and the United States but also among European states themselves. This raises the pivotal question of economic sustainability. Many NATO member countries face profound fiscal constraints, exacerbated by inflation, energy crises, and stagnating GDP growth. Balancing these pressures against an amplified call for defense expenditures is a herculean task, especially for smaller and mid-sized economies like Bulgaria, Latvia, and Slovenia.

In this context, NATO’s capacity to craft multilateral funding mechanisms emerges as a cornerstone of strategic sustainability. While wealthier members such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom possess the industrial and economic base to absorb increased contributions, the alliance must confront disparities that place disproportionate strain on its economically weaker allies. The integration of a centralized financial redistribution model, one that accounts for each member’s fiscal capacity, is paramount. Without such an approach, the vision of a fully interoperable and equitably resilient NATO risks disintegration under the weight of internal disparities.

Simultaneously, Rutte’s forewarning underscores an acute vulnerability within Europe’s defense apparatus: its fragmented procurement systems and reliance on external military-industrial bases. Over decades, NATO has struggled to overcome inefficiencies rooted in national silos of production, procurement, and innovation. For example, while the United States remains the dominant provider of military hardware and technologies, European members lack cohesive frameworks to independently sustain high-intensity military operations. This imbalance underscores the urgency of establishing integrated defense production strategies, enabling Europe to gradually reduce its reliance on U.S.-centric supply chains without sacrificing operational readiness.

Equally important is the broader geopolitical impact of Rutte’s statements. The specter of reduced U.S. involvement in European security has become increasingly plausible amidst shifting political landscapes in Washington. This shift compels European NATO members to accelerate their transition toward autonomous defense infrastructures while simultaneously maintaining the collaborative integrity of the alliance. The paradox, however, lies in the necessity for Europe to expand its defense budgets at precisely the moment when domestic political resistance to such measures is mounting. Public dissatisfaction with high inflation, unemployment, and strained public services could undermine efforts to mobilize political and financial support for increased military investments.

Another dimension that must be critically analyzed is the role of defense innovation in bridging capability gaps within NATO. For Europe, this translates to advancing cutting-edge technologies—cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, and space defense—to not only meet NATO’s immediate operational demands but also to future-proof its strategic capabilities against next-generation threats. The establishment of collaborative research and development hubs across Europe, linked directly to NATO’s defense innovation programs, offers a pathway to cost-efficient technological competitiveness. Moreover, joint procurement agreements focusing on high-value assets—such as advanced surveillance systems and integrated missile defense platforms—must be a cornerstone of these efforts. Without robust investments in these domains, Europe’s ability to operate independently from its U.S. counterpart remains aspirational at best.

These defense advancements, however, require not just financial commitments but political foresight and institutional restructuring. One of NATO’s enduring challenges has been the lack of operational coherence among its member states’ defense strategies. For the alliance to evolve, there must be an unprecedented alignment of national defense policies, ensuring that investments are not duplicated but are instead targeted at areas of collective vulnerability. Initiatives like NATO’s Defense Planning Process must become more rigorous in setting enforceable benchmarks that address critical gaps in capabilities, readiness, and response times.

Moreover, the global implications of NATO’s recalibration cannot be overstated. As Rutte’s remarks indicate, NATO’s evolving dynamics resonate far beyond its immediate geographic confines. The United States, for all its emphasis on encouraging European self-reliance, remains a critical global arbiter of security, countering threats from China, Iran, and other state and non-state actors. Simultaneously, NATO’s pivot toward greater European responsibility sends a potent signal to adversaries, affirming the alliance’s unity and adaptability in the face of multifaceted threats. Yet, this pivot also raises the specter of an arms race, particularly with Russia’s ongoing militarization and China’s expanding geopolitical ambitions. The ripple effects of NATO’s enhanced defense posture will undoubtedly shape global military-industrial trends, alliances, and rivalries for decades to come.

Lastly, NATO’s internal recalibration must grapple with its enduring identity. While the 5% GDP defense mandate symbolizes a bold and necessary response to an increasingly unstable world, it also forces the alliance to confront its most existential questions: How can NATO sustain its relevance as a collective defense entity when member states increasingly prioritize national over collective interests? How does the alliance reconcile its short-term needs for increased spending with its long-term mission of promoting peace and stability? These questions demand not just policy solutions but a reinvigoration of NATO’s founding ethos—a commitment to unity, resilience, and the preservation of liberal-democratic values.

The implications of Mark Rutte’s remarks thus extend well beyond the immediate logistics of financing military supplies for Ukraine. They encapsulate the broader challenge of redefining NATO’s role in a world where economic pressures, technological disruptions, and shifting political allegiances demand a reinvention of traditional security paradigms. As NATO navigates this tumultuous era, its ability to adapt—economically, strategically, and ideologically—will determine its legacy as the vanguard of transatlantic security.

Reinforcing Strategic Autonomy: The Path Towards European Defense Integration

The current dynamics within NATO reflect a critical juncture in Europe’s pursuit of greater strategic autonomy. The shifting security landscape, compounded by intensifying geopolitical challenges, has brought into sharp focus the imperative for Europe to recalibrate its defense framework. This recalibration is not merely a reaction to external pressures but an intrinsic necessity for aligning Europe’s military objectives with its long-term economic and political ambitions. The question at the heart of this evolution is how European nations can establish a robust, cohesive defense strategy that harmonizes their individual interests while strengthening collective security.

At its core, the drive for European defense integration underscores the need to overcome persistent inefficiencies in resource allocation and capability development. For decades, the absence of a unified approach has resulted in duplication of efforts, fragmented procurement processes, and significant disparities in military readiness across the continent. Countries with smaller economies and limited defense budgets, such as Slovenia and Bulgaria, face structural constraints that inhibit their ability to independently modernize their forces. Meanwhile, wealthier nations like Germany and France have often pursued divergent priorities, further complicating efforts to establish a coherent European defense architecture.

To address these systemic challenges, the establishment of a centralized European defense procurement mechanism emerges as a critical solution. Such a mechanism would enable member states to pool resources, negotiate collective contracts, and streamline production pipelines for key military assets. For instance, the development of next-generation fighter jets, advanced missile defense systems, and cyber capabilities could be coordinated under a unified framework, significantly reducing costs while enhancing interoperability. Moreover, a centralized procurement strategy would mitigate the inefficiencies associated with national silos, ensuring that investments are directed towards capabilities that address NATO’s most pressing strategic vulnerabilities.

The success of this approach, however, hinges on the political will of European leaders to transcend nationalistic tendencies and embrace a collaborative ethos. Historically, attempts to forge greater defense cooperation have been stymied by competing interests and bureaucratic inertia. The European Defence Fund (EDF) represents a promising step in this direction, yet its scope and funding remain limited relative to the scale of Europe’s security challenges. Expanding the EDF’s mandate, coupled with increased financial contributions from member states, could serve as a catalyst for deeper integration. Additionally, fostering partnerships with private sector innovators is essential for bridging the technological gaps that currently hinder Europe’s ability to compete with global adversaries.

Beyond the economic and technological dimensions, the pursuit of European defense integration carries profound implications for NATO’s operational cohesion. As Europe assumes greater responsibility for its security, the alliance must adapt to a redefined transatlantic dynamic. The balance between European autonomy and NATO’s collective framework will require careful calibration to ensure that efforts to enhance Europe’s self-reliance do not undermine the alliance’s overarching objectives. This balance can be achieved through a dual-track approach: strengthening Europe’s independent capabilities while maintaining close coordination with the United States and other non-European allies.

The strategic calculus driving this shift extends beyond Europe’s immediate security concerns. The rise of asymmetric threats, such as cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns, underscores the importance of non-traditional defense measures that complement conventional military capabilities. In this context, Europe’s emphasis on digital resilience, intelligence sharing, and counter-hybrid warfare strategies will play a pivotal role in shaping NATO’s future posture. These efforts must be supported by investments in cutting-edge technologies, robust legal frameworks, and enhanced coordination among intelligence agencies across member states.

Equally important is the role of public engagement in sustaining the momentum for European defense integration. The economic and social sacrifices associated with increased defense spending necessitate transparent communication and inclusive policymaking. Governments must articulate the long-term benefits of enhanced security, not only in terms of deterring aggression but also in fostering stability and economic growth. By framing defense investments as integral to broader national development goals, policymakers can build public consensus and mitigate resistance to potentially contentious fiscal adjustments.

The path towards European defense integration also intersects with broader geopolitical considerations. As the global power balance continues to shift, Europe must navigate an increasingly multipolar world marked by the resurgence of great-power competition. Strengthening transatlantic ties remains vital, yet Europe must also engage with emerging powers to diversify its strategic partnerships. Initiatives such as deepened cooperation with Indo-Pacific democracies, expanded dialogue with African nations, and strategic engagement with Latin American countries reflect the need for a more globally oriented European defense policy.

The challenges inherent in this transformation are immense, yet they are matched by equally significant opportunities. By embracing a comprehensive approach that aligns economic, technological, and political dimensions, Europe can lay the foundation for a defense strategy that is both sustainable and adaptive. This vision requires a collective commitment to overcoming historical divisions, fostering innovation, and prioritizing resilience in the face of evolving threats. Ultimately, the pursuit of European defense integration is not merely a strategic imperative but a testament to Europe’s determination to uphold its role as a pillar of global security in the 21st century.

Strategic Adaptation and the Shifting Paradigm of U.S. Influence in NATO

The evolving dynamics of transatlantic security underscore a pivotal transformation in the strategic role of the United States within NATO. As geopolitical tensions intensify and economic considerations increasingly dominate policymaking, the long-standing equilibrium between American leadership and European reliance is being recalibrated. This reconfiguration demands a nuanced analysis of how the United States can adapt its defense strategies, resource allocation, and diplomatic priorities to sustain its influence while accommodating the growing calls for equitable burden-sharing among NATO allies.

Central to this shift is the complex interplay between U.S. military capabilities and its broader foreign policy objectives. The United States’ unmatched capacity to project power globally has positioned it as the cornerstone of NATO’s operational framework. Advanced military technologies, extensive logistical networks, and unparalleled intelligence capabilities have enabled the alliance to respond effectively to a wide range of threats. However, these capabilities are not inexhaustible, and the financial and political costs of maintaining such dominance are becoming increasingly apparent.

The Ukraine conflict, while reaffirming the indispensability of U.S. support, has also exposed the limits of unilateral action in a multipolar world. The financial burden of supplying Ukraine with advanced weaponry, including precision-guided munitions and anti-aircraft systems, has raised questions about the sustainability of current U.S. defense spending levels. With a defense budget exceeding $800 billion annually, the United States already allocates more resources to its military than the next ten nations combined. Meeting additional demands for NATO operations, while simultaneously addressing domestic priorities such as infrastructure modernization and healthcare reform, presents a significant challenge for American policymakers.

This fiscal strain is compounded by shifting domestic attitudes towards foreign intervention. The legacy of protracted conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan has fueled skepticism among American voters regarding extensive overseas commitments. This sentiment has been further amplified by political factions advocating for a more isolationist approach, emphasizing the need to prioritize domestic concerns over international obligations. The emergence of these narratives has profound implications for NATO, as they risk undermining the transatlantic unity that has long been the alliance’s foundation.

In response to these challenges, the United States must adopt a strategic approach that balances its leadership role within NATO with the realities of an evolving global order. One critical element of this strategy is the recalibration of defense spending to emphasize high-impact, cost-effective initiatives. Investments in emerging technologies, such as autonomous systems, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence, can enhance the efficiency and precision of military operations, reducing the need for extensive personnel deployments and minimizing logistical costs. By leveraging its innovation-driven economy, the United States can maintain its strategic edge while alleviating some of the financial pressures associated with traditional military commitments.

Another key aspect of this recalibration is the fostering of greater interoperability among NATO members. While the United States has historically been the primary supplier of military hardware and expertise within the alliance, the emphasis must now shift towards empowering European allies to assume a more active role in collective defense. Initiatives such as joint training programs, standardized equipment specifications, and integrated command structures can enhance the operational cohesion of NATO forces, ensuring that the alliance remains capable of addressing both conventional and unconventional threats.

Equally important is the role of diplomatic engagement in reinforcing transatlantic solidarity. The United States must navigate the delicate balance between encouraging greater European autonomy and maintaining its leadership position within NATO. This requires a collaborative approach that respects the sovereignty and agency of European nations while promoting shared values and objectives. High-level consultations, bilateral agreements, and multilateral forums provide platforms for fostering consensus and addressing potential points of contention, ensuring that NATO’s strategic vision remains aligned with the interests of all member states.

The implications of these adjustments extend beyond the immediate context of the Ukraine conflict. As global power dynamics continue to evolve, NATO faces the dual challenge of countering traditional adversaries such as Russia while addressing emerging threats from non-state actors, cyberattacks, and climate-induced instability. The United States’ ability to adapt its role within the alliance is therefore critical not only for the future of NATO but also for the broader stability of the international system. By embracing a forward-looking and inclusive approach, the United States can reinforce its commitment to transatlantic security while laying the groundwork for a more balanced and resilient alliance.

Decoding Russia’s Strategic Calculations and Geopolitical Maneuvering in the Ukraine Conflict

Russia’s response to Western military aid to Ukraine highlights a deliberate strategy rooted in a complex interplay of military assertiveness, economic coercion, and strategic disinformation. At the heart of Moscow’s approach lies the dual objective of undermining NATO’s cohesion while bolstering its own narrative of legitimacy on the global stage. Russia’s position, articulated through official rhetoric and state-sponsored media, reflects an attempt to consolidate domestic support, galvanize geopolitical alliances, and challenge the existing international order. This phase of the conflict demands an intricate examination of Russia’s underlying motivations, its calculated maneuvers, and their broader implications.

Central to Russia’s strategic calculations is the portrayal of NATO’s support for Ukraine as not merely an act of solidarity but as a direct affront to Russia’s sovereignty and security. By framing the conflict as a proxy war orchestrated by NATO, Moscow seeks to delegitimize Western involvement and reframe its aggression as a defensive measure. This narrative aligns with longstanding Russian claims that NATO’s eastward expansion constitutes a violation of prior agreements and a strategic encroachment on Russia’s sphere of influence. Such rhetoric is not purely reactionary but forms part of a broader campaign to erode Western unity by amplifying divisions within NATO and exploiting the war-weariness of its member states.

Beyond rhetorical posturing, Russia’s strategic maneuvers encompass a calculated use of military and paramilitary tactics designed to sustain pressure on Ukraine while signaling its resolve to NATO. The persistent targeting of Ukraine’s critical infrastructure, including energy grids, transportation networks, and communication systems, reflects a strategy aimed at weakening Kyiv’s resilience and complicating NATO’s logistical and operational support. Simultaneously, Moscow has leveraged non-conventional assets, such as the Wagner Group and other proxy forces, to exert influence in contested regions, extending its reach without overtly escalating direct military confrontations.

However, the effectiveness of Russia’s military strategy has been increasingly constrained by the limitations of its industrial base and the evolving nature of modern warfare. The reliance on aging equipment and conscript forces underscores systemic challenges within Russia’s defense apparatus, compounded by the impact of Western sanctions on its access to critical technologies. To counter these limitations, Moscow has sought to deepen its partnerships with non-Western allies, particularly China and Iran, for military and technological support. These alliances, though fraught with asymmetrical dynamics, have provided Russia with a lifeline in its pursuit of strategic endurance.

The economic dimension of Russia’s strategy is equally significant, as the Kremlin has sought to leverage its vast energy resources to exert influence over Europe and other key regions. The weaponization of natural gas and crude oil supplies, exemplified by the deliberate throttling of pipelines and price manipulations, has underscored the vulnerabilities of Europe’s energy dependencies. While these tactics have caused significant disruptions, they have also accelerated Europe’s diversification efforts, prompting investments in renewable energy, liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports, and expanded storage capacities. For Russia, the long-term consequences of this shift represent a strategic dilemma, as its economic reliance on fossil fuel exports faces increasing constraints in a decarbonizing global economy.

Moreover, Moscow’s economic coercion extends beyond energy to encompass broader trade and financial mechanisms. The Kremlin has sought to establish alternative financial systems, such as the Mir payment network and bilateral trade agreements denominated in local currencies, to circumvent Western sanctions. While these initiatives have had limited success in mitigating the immediate impact of sanctions, they signal Russia’s intent to challenge the dominance of Western-controlled financial systems. However, the sustainability of such measures remains questionable, given the structural weaknesses of Russia’s economy, including its dependence on raw material exports and limited industrial diversification.

Russia’s attempts to galvanize international support in the Global South form another pillar of its strategy. By portraying itself as a counterweight to Western dominance, Moscow has sought to cultivate relationships with emerging economies and position itself as a champion of multipolarity. This narrative has resonated in some quarters, particularly among nations critical of Western interventions and historical colonialism. However, Russia’s ability to translate rhetorical solidarity into substantive alliances has been constrained by its limited economic and diplomatic leverage compared to major players like China and the United States.

The implications of Russia’s strategy extend beyond the immediate context of the Ukraine conflict. Moscow’s actions have underscored the interconnectedness of military, economic, and informational dimensions in contemporary geopolitics, challenging traditional paradigms of power and influence. For NATO and its allies, countering Russia’s maneuvers requires a comprehensive approach that integrates military deterrence, economic resilience, and strategic communication. Strengthening supply chains, enhancing the interoperability of forces, and investing in counter-disinformation capabilities are critical components of this response.

At the same time, the broader international community faces the challenge of addressing the structural drivers of the conflict while mitigating its ripple effects. The erosion of trust in international norms, the fragmentation of multilateral institutions, and the intensification of great-power rivalries highlight the need for a renewed commitment to diplomacy and conflict resolution. For Russia, the long-term viability of its strategy hinges on its ability to adapt to a rapidly changing global landscape, where economic isolation and military overstretch could undermine its aspirations for sustained influence.

In sum, Russia’s perspective on the Ukraine conflict is shaped by a complex interplay of historical grievances, strategic imperatives, and geopolitical ambitions. Its actions, while reflecting a calculated pursuit of immediate objectives, also expose deeper vulnerabilities that could reshape its position in the global order. As the conflict continues to evolve, the strategic calculus for all stakeholders will remain fluid, demanding vigilance, adaptability, and a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted dynamics at play.

Recalibrating the Global Order: Strategic Realignments and Emerging Security Paradigms

The reverberations of the Ukraine conflict have catalyzed a profound transformation in the architecture of international security, demanding a recalibration of strategic priorities and alliances on a global scale. At its core, this conflict has revealed not only the fragility of existing geopolitical frameworks but also the urgency of addressing systemic vulnerabilities that transcend regional boundaries. As nations grapple with the intricate interplay of military, economic, and political imperatives, the contours of a new global order are beginning to take shape, characterized by shifting alliances, contested spheres of influence, and the redefinition of strategic objectives.

A pivotal aspect of this transformation lies in the diversification of global security alliances beyond their traditional configurations. The conflict has underscored the limitations of regionally focused defense mechanisms, propelling states to forge partnerships that transcend geographic boundaries. For instance, the strengthening of ties between NATO and Indo-Pacific democracies, such as Japan and Australia, signals the emergence of a more interconnected security framework that seeks to address the dual threats of military aggression and coercive economic practices. These alignments underscore the necessity of adopting a holistic approach to security, one that integrates defense capabilities with economic and technological resilience.

This evolving paradigm also reflects the increasing prominence of energy security as a cornerstone of geopolitical strategy. The Ukraine conflict has disrupted established energy supply chains, prompting a reevaluation of dependencies on fossil fuels and accelerating the transition toward renewable energy sources. For Europe, this shift represents a strategic opportunity to achieve greater energy autonomy, reduce vulnerabilities to external coercion, and position itself as a leader in the global energy transition. However, the path to energy independence is fraught with challenges, including the need to balance environmental imperatives with the economic realities of transitioning away from entrenched fossil fuel infrastructures.

The recalibration of energy policies is not confined to Europe; it resonates globally, with significant implications for the geopolitical influence of energy-producing nations. Russia’s diminishing role as a primary supplier to Europe is counterbalanced by the rise of alternative producers, such as the United States, Qatar, and Australia, which are expanding their share of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) market. Additionally, the acceleration of investments in green hydrogen, battery storage technologies, and cross-border energy grids underscores the strategic dimension of clean energy innovation as a tool for reshaping power dynamics.

Beyond energy, the conflict has reignited discussions on the resilience of global supply chains and the strategic implications of economic interdependence. The disruptions caused by the conflict, exacerbated by sanctions on Russia and countermeasures targeting Western economies, have highlighted the risks inherent in concentrated trade dependencies. Nations are increasingly adopting “friend-shoring” strategies, prioritizing trade and supply chain relationships with allied states to mitigate geopolitical risks. This trend not only reshapes global trade flows but also raises questions about the balance between economic efficiency and strategic security in an era of heightened geopolitical competition.

The reconfiguration of global trade also intersects with the technological dimensions of security, particularly the race to dominate emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and space exploration. The conflict has demonstrated the critical role of advanced technologies in modern warfare, from precision-guided munitions to cyber operations. This technological arms race extends beyond the battlefield, influencing the economic competitiveness and geopolitical influence of states. For NATO, integrating cutting-edge technologies into its strategic framework is imperative to maintain its relevance and effectiveness in addressing both conventional and asymmetric threats.

China’s response to the Ukraine conflict exemplifies the complexities of navigating the intersection of economic, technological, and military competition in a multipolar world. While maintaining a nominal stance of neutrality, Beijing has sought to balance its strategic partnership with Russia against its economic interdependence with the West. This delicate maneuvering underscores the broader challenge faced by emerging powers in aligning their geopolitical objectives with their economic interests. For NATO and its allies, engaging with these nations requires a nuanced approach that emphasizes the shared benefits of stability and cooperation while addressing the underlying drivers of great-power rivalry.

The implications of these dynamics are particularly pronounced in the Global South, where the conflict has exacerbated existing vulnerabilities related to food security, energy access, and economic inequality. The disruption of agricultural exports from Ukraine and Russia has contributed to rising global food prices, disproportionately affecting developing nations. This crisis underscores the interconnectedness of security challenges, highlighting the need for comprehensive strategies that address the root causes of instability. For NATO, this entails expanding its role beyond traditional military domains to include contributions to global stability through humanitarian assistance, capacity-building, and resilience-enhancing initiatives.

The redefinition of global security also demands a reevaluation of the role of multilateral institutions in fostering cooperation and mitigating conflicts. The limitations of existing frameworks, exemplified by the gridlock within the United Nations Security Council, underscore the need for innovative approaches to global governance. Initiatives such as regional security forums, hybrid alliances, and issue-specific coalitions offer potential pathways for addressing emerging challenges. However, their effectiveness hinges on the ability of participating states to reconcile divergent interests and prioritize collective goals over unilateral agendas.

In this context, NATO’s role as a pillar of transatlantic security takes on heightened significance. The alliance must navigate the dual imperatives of adapting to a rapidly changing global landscape while reinforcing its foundational principles of collective defense and cooperative security. This necessitates a proactive approach to strategic planning, one that anticipates future challenges and aligns resources with priorities. By fostering innovation, strengthening partnerships, and enhancing its operational adaptability, NATO can position itself as a central actor in shaping the emerging global order.

As the contours of this new order continue to evolve, the interplay of military, economic, and technological factors will define the trajectory of global security. The Ukraine conflict serves as both a catalyst and a microcosm of these broader dynamics, highlighting the urgency of proactive engagement and strategic foresight. For nations and alliances alike, the challenge lies not only in responding to immediate threats but also in building a resilient framework capable of addressing the complexities of an interconnected and rapidly transforming world.

The Strategic Balance of Economic Pressure and Diplomatic Engagement in Geopolitical Conflict

The use of economic measures as a lever for geopolitical influence has become increasingly central in the strategies of major powers, particularly in the context of the Ukraine conflict. This evolving dynamic underscores the intricate balance between imposing economic sanctions and fostering diplomatic channels to achieve strategic goals. Donald Trump’s proposed escalation of sanctions and tariffs against Russia represents a notable shift in the global approach to conflict resolution, emphasizing the potential of economic isolation to compel behavioral change. However, the implications of such measures are far-reaching, impacting not only bilateral relations but also the broader structure of international economic and political alignments.

The Fragility of Russia’s Economic Framework Under Heightened Sanctions

Russia’s economy, heavily reliant on exports of energy resources, raw materials, and agricultural products, faces significant vulnerabilities under the weight of existing and proposed sanctions. While strategic partnerships with nations such as China and India have provided Moscow with alternative trade avenues, these relationships are constrained by logistical challenges, limited market capacity, and the geopolitical complexities of secondary sanctions. Any additional escalation in economic isolation, including comprehensive bans on remaining export channels or heightened tariffs targeting Russian goods, would exacerbate fiscal pressures on the Kremlin.

The contraction of Russian GDP since the onset of sanctions in 2022 highlights the acute economic repercussions of these measures. With diminished foreign investment and restricted access to global financial systems, the Kremlin has resorted to domestic economic interventions, such as the nationalization of key industries and increased reliance on its sovereign wealth fund. However, these efforts offer limited respite against the compounded effects of declining revenues, technological isolation, and capital flight. The introduction of secondary sanctions targeting countries that facilitate trade with Russia could further destabilize its economic position, amplifying the strain on critical sectors such as energy and manufacturing.

Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Economic Contagion Risks

The cascading impact of economic sanctions on Russia extends beyond its borders, reverberating through global supply chains and international markets. Critical sectors such as agriculture, energy, and industrial production are particularly susceptible to disruptions, as evidenced by the volatility in global grain and energy prices following the imposition of initial sanctions. For countries in the Global South, which rely on imports of Russian fertilizers and agricultural products, these disruptions exacerbate existing vulnerabilities related to food security and economic stability.

Furthermore, the alignment of Western allies in imposing coordinated sanctions has intensified fragmentation within the global trading system, as nations outside the NATO sphere navigate competing pressures to maintain neutrality or align with one of the opposing blocs. The strategic recalibration of trade partnerships, exemplified by Russia’s pivot towards Asia and Africa, underscores the geopolitical realignments triggered by economic measures. For the United States and its allies, mitigating the broader economic fallout of sanctions requires a multifaceted approach that includes targeted aid to affected regions, diversification of global supply chains, and sustained dialogue with key trade partners.

Diplomatic Leverage Through Economic Measures: Opportunities and Challenges

The use of economic sanctions as a diplomatic tool presents both opportunities and challenges in the pursuit of conflict resolution. On one hand, the imposition of financial constraints on adversarial states can serve as a powerful deterrent against aggressive actions, signaling the unified resolve of the international community. On the other hand, the potential for sanctions to entrench resistance and incentivize alternative alignments necessitates careful calibration of their scope and implementation.

In the context of the Ukraine conflict, the strategic deployment of sanctions must be complemented by diplomatic efforts to engage with neutral or non-aligned states, fostering a consensus-driven approach to conflict resolution. The role of multilateral institutions, such as the United Nations and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), is critical in facilitating dialogue and mediating disputes. However, the effectiveness of these institutions is contingent upon the willingness of major powers to prioritize collective security objectives over unilateral interests.

Repercussions for U.S. Domestic and Foreign Policy

For the United States, the pursuit of an aggressive sanctions regime against Russia carries significant implications for both domestic and foreign policy. Domestically, the economic consequences of such measures, including inflationary pressures and increased costs for consumers and businesses, necessitate proactive mitigation strategies. Investments in energy independence, technological innovation, and industrial resilience are critical to ensuring that the U.S. economy remains robust in the face of global economic volatility.

On the international front, the escalation of economic measures underscores the importance of maintaining strategic alliances and fostering multilateral cooperation. The credibility of U.S. leadership in shaping global norms and advancing democratic values hinges on its ability to navigate the complexities of modern statecraft, balancing hard power with soft power and addressing the root causes of conflict through a comprehensive and inclusive approach.

Strategic Considerations for NATO’s Collective Response

The implications of U.S.-led economic measures extend to NATO’s collective strategy, necessitating a coordinated response that aligns military objectives with economic and diplomatic initiatives. The alliance’s ability to project power and deter aggression depends not only on its military capabilities but also on its capacity to leverage economic tools as a complement to traditional defense mechanisms. Joint procurement initiatives, technological collaborations, and shared intelligence platforms are critical to enhancing NATO’s strategic coherence and operational effectiveness.

Moreover, the integration of economic measures into NATO’s strategic framework underscores the importance of burden-sharing and equitable contributions among member states. The disproportionate reliance on U.S. leadership in implementing sanctions highlights the need for European allies to assume a more proactive role in addressing shared security challenges. By aligning economic policies with broader strategic objectives, NATO can strengthen its collective resilience and reinforce its commitment to upholding international norms and values.

The Path Forward: Balancing Economic Pressure and Diplomatic \Engagement

The trajectory of U.S.-Russia dynamics amid the Ukraine conflict highlights the intricate interplay between economic leverage and diplomatic engagement in shaping the global security landscape. The strategic deployment of economic measures, while a powerful tool in exerting pressure on adversarial states, must be accompanied by a nuanced understanding of their broader implications. The success of these measures depends on their ability to achieve tangible outcomes, such as de-escalation of hostilities and the establishment of a sustainable framework for peace.

In pursuing these objectives, the United States and its allies must navigate a complex web of geopolitical interests, balancing short-term tactical gains with long-term strategic stability. The integration of economic, military, and diplomatic tools into a cohesive strategy is essential to addressing the multifaceted challenges of modern conflict and fostering a resilient and inclusive global order.

Economic Dimensions of Sanctions and Global Realignments in the Ukraine Conflict

The economic dimensions of the Ukraine conflict remain pivotal in shaping the global geopolitical order. With the United States leading efforts to isolate Russia economically, the direct and cascading effects of sanctions require precise evaluation. For 2022, Russian GDP contracted by 2.1%, with the International Monetary Fund projecting a further constrained annual growth rate of 0.7% for 2023 under current sanctions. These figures underscore the vulnerability of Russia’s $2.3 trillion economy, which relies on commodity exports, primarily energy, metals, and agriculture.

Impact on Russia’s Energy Sector

Russia’s oil and gas revenues accounted for 42% of the federal budget before the war, amounting to $333 billion annually. Sanctions targeting energy exports have reduced revenue flows drastically. The European Union’s decision to cut oil imports by 90% by the end of 2023 (from 2021 levels) has forced Russia to redirect sales to countries like China and India at discounted rates. For instance, Russian crude oil, sold at a global benchmark price of $80 per barrel, trades at $55-$60 per barrel for Asian buyers, reducing profits by at least 25% per barrel.

Furthermore, sanctions on liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports have disrupted Russia’s access to critical European markets, which accounted for 32% of Gazprom’s sales in 2021. The Nord Stream 2 pipeline suspension alone is estimated to cost Russia $11 billion in sunk investments. With limited infrastructure for redirecting gas to alternative markets, these losses will likely widen, further constraining Moscow’s fiscal capacities.

Financial Repercussions on Global Trade and Supply Chains

Sanctions against Russian commodities, including metals such as palladium and nickel, have disrupted global supply chains. Russia supplies 44% of the world’s palladium—a critical input for catalytic converters in the automotive industry. A 30% decline in Russian palladium exports has contributed to a 19% global price surge in 2023, affecting automobile production costs.

Similarly, the restriction of Russian fertilizer exports has caused prices to soar, impacting agricultural output globally. Fertilizer prices increased by 29% in 2022, driving food inflation, particularly in developing economies that depend heavily on Russian exports. This has exacerbated global food insecurity, with the United Nations estimating that an additional 50 million people have been pushed into acute hunger due to the ripple effects of sanctions.

Quantitative Analysis of U.S. Sanctions and Financial Isolation

The United States’ imposition of financial sanctions on Russian banks has effectively barred them from the SWIFT system, cutting off 70% of Russia’s banking sector from international markets. This has reduced foreign currency reserves accessible to the Russian central bank by $300 billion, leaving Moscow with just $130 billion in liquid assets as of 2023. Combined with restricted access to Western credit markets, Russia’s sovereign credit rating has been downgraded to CCC+ by S&P, reflecting near-junk status.

These financial measures have also triggered substantial capital outflows, with over $90 billion in foreign direct investment exiting Russia between 2022 and 2023. The exodus of Western corporations, including over 1,000 major firms such as McDonald’s, ExxonMobil, and IKEA, has further hollowed out Russia’s economic landscape. The Kremlin faces escalating unemployment, with job losses exceeding 2.7 million in sectors reliant on Western investment.

Broader Economic Costs and NATO’s Collective Contributions

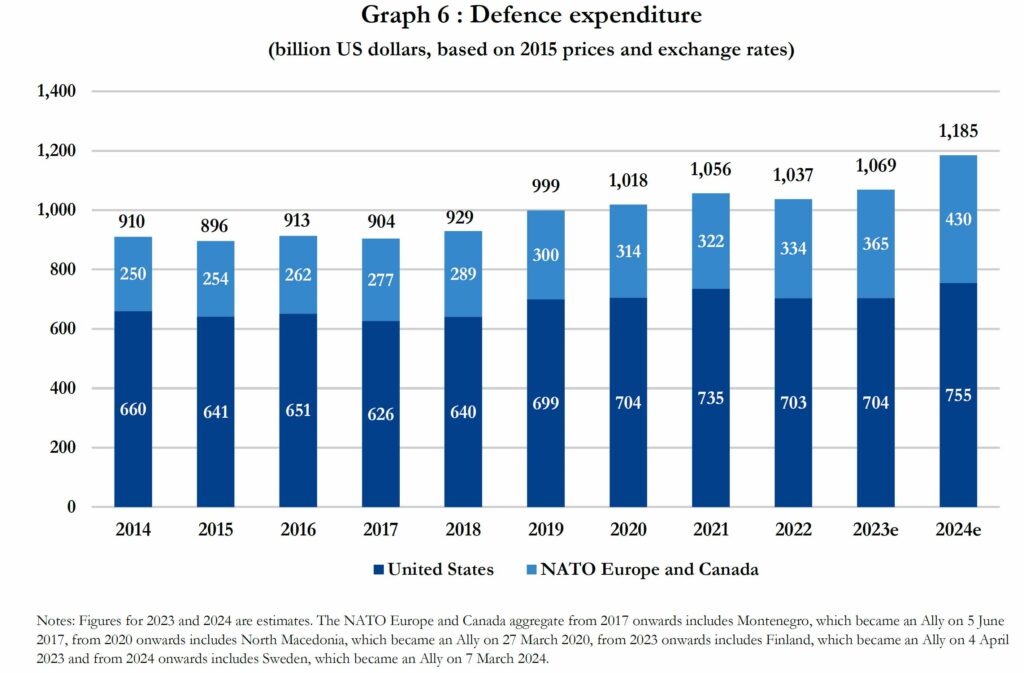

The fiscal response of NATO member states to the Ukraine conflict, particularly in defense budgets and humanitarian aid, has exceeded $150 billion as of mid-2023. The United States alone has provided $48 billion in military assistance, accounting for 68% of NATO’s total contributions. European NATO allies, including Germany, the UK, and Poland, have collectively pledged an additional $43 billion, with significant investments in upgrading their military capabilities.

Quantified NATO Contributions: Key Member States

- Germany: Increased its defense spending to €100 billion ($107 billion) in 2023, up from €50 billion pre-war, reflecting a doubling of military investments. These funds are allocated toward modernizing tank fleets, upgrading air defenses, and procuring U.S.-made F-35 fighter jets.

- Poland: Allocated 4% of GDP to defense in 2023, amounting to $35 billion, with purchases including 500 HIMARS rocket systems and 250 Abrams tanks, positioning Poland as NATO’s eastern bulwark.

- France: Committed €44 billion ($47 billion) in 2023 to defense, focusing on expanding naval and cyber capabilities, with an emphasis on deterrence in the Mediterranean.

- UK: Allocated £55 billion ($69 billion) in defense spending, with strategic investments in nuclear deterrence and maritime security in the North Atlantic.

Economic Ramifications for NATO States Meeting 5% Mandate

If all NATO members meet the 5% GDP defense spending mandate, the total NATO-wide defense budget would rise to $2.2 trillion annually, up from the current $1.1 trillion. This would necessitate additional allocations totaling $1.1 trillion across 32 member states, with substantial fiscal impacts on both smaller and larger economies:

- United States: Defense spending would increase by $468 billion annually, reaching $1.436 trillion, representing a 54% rise in military expenditures.

- Germany: Required spending would rise from $107 billion to $230 billion, an increase of $123 billion annually, challenging its debt-to-GDP ratio currently at 66%.

- Italy: Defense spending would increase by $81 billion, reaching $115 billion, representing a quadrupling of current investments, potentially triggering austerity measures.

- Latvia: With a GDP of $45 billion, Latvia would need to allocate $2.25 billion to defense, representing a 65% increase in annual spending.

- Montenegro: Required defense spending of $400 million would represent a 147% increase, necessitating substantial external support to maintain economic stability.

Economic Adjustments and Strategic Implications

To meet these financial requirements, member states must navigate complex domestic and international trade-offs:

- Tax Policy Adjustments: Larger economies like France and Germany may increase defense-focused taxation or redirect funds from other sectors, including education and healthcare.

- Debt Financing: Countries with constrained fiscal space, such as Greece and Portugal, are likely to rely on sovereign debt, potentially exacerbating public debt levels, which currently stand at 194% and 128% of GDP, respectively.

- Economic Multiplier Effects: Increased military expenditures could stimulate defense-related industries, with multiplier effects on employment and technological innovation. However, smaller economies may experience economic overheating if funds are drawn disproportionately from domestic resources.

The Kremlin’s Geopolitical Calculus Under Economic Strain

The Kremlin’s multifaceted approach to navigating the intensifying economic and geopolitical pressures underscores its reliance on strategic adaptability amidst an increasingly constrained environment. As U.S.-led sanctions tighten, and NATO solidarity strengthens, Russia’s strategic recalibrations have entered a complex and precarious phase. Central to these adaptations is Moscow’s attempt to realign its geopolitical relationships, fortify internal economic mechanisms, and project an image of resilience both domestically and internationally.

Russia’s economic diversification strategy, while partially effective, is inherently hindered by limitations in infrastructure, technological dependence, and geopolitical constraints. Trade redirection efforts, primarily targeting Asia and the Middle East, demonstrate both ingenuity and desperation. For instance, exports to China surged to record highs in 2023, with bilateral trade between the two nations exceeding $190 billion, propelled by discounted oil and gas sales. However, this shift in focus exposes vulnerabilities, particularly as Russia forfeits revenue by trading resources below global market rates to maintain market share in less profitable regions.

Similarly, efforts to expand trade with India, especially in defense and energy, have gained momentum. Russian arms exports to India grew by over 20% between 2022 and 2023, largely facilitated through agreements circumventing dollar-based payments. Yet, the reliance on barter trade and rupee-based transactions has posed challenges for Russia, constraining its ability to repatriate earnings and weakening its overall fiscal position.

Internal Stabilization Efforts and Their Shortcomings

Domestically, the Russian government has implemented aggressive fiscal policies to mitigate the immediate impacts of sanctions. Increased public spending in military production, agriculture, and domestic manufacturing reflects a deliberate shift toward self-sufficiency. For example, Russia allocated nearly 25% of its national budget to defense in 2023, marking a sharp increase from previous years. While this has bolstered domestic arms production and ensured continued operations on the battlefield, it has exacerbated inflationary pressures and widened socioeconomic inequalities.

Inflation in Russia reached 12.5% in 2023, driven by higher costs of imports and supply chain disruptions. Price hikes on essential goods, such as food and medicine, have disproportionately affected low-income households, intensifying public discontent. Though the Kremlin has introduced price caps on key commodities and expanded subsidies for vulnerable populations, these measures remain insufficient to address the broader economic contraction, which saw GDP shrink by 2.1% in 2022 and stagnate in 2023.

Leveraging Strategic Resources for Influence

Russia’s enduring reliance on its energy sector as a geopolitical tool underscores the limitations of its diversification strategy. Despite losing access to European markets, Russian oil and gas revenues still account for approximately 35% of federal income. The Kremlin has sought to weaponize this dependency, particularly through threats of gas supply disruptions during the winter months. These tactics, while temporarily effective in 2022, have diminished in impact as European nations reduce their reliance on Russian energy, achieving a 25% drop in gas imports from Russia by late 2023. Countries such as Germany and Italy have fast-tracked investments in renewable energy and alternative suppliers, significantly weakening Moscow’s leverage.

In addition to energy, Russia has attempted to exert influence through the export of critical raw materials. As one of the world’s largest producers of nickel, palladium, and wheat, Russia wields significant influence over global markets. For instance, disruptions to Russian wheat exports contributed to a 14% increase in global grain prices in 2023, exacerbating food insecurity in developing nations. However, the Kremlin’s ability to sustain such leverage is constrained by logistical challenges and countermeasures from Western nations, including increased production subsidies and strategic reserves.

Military and Geopolitical Repositioning

Militarily, Russia has pursued strategies to mitigate the operational constraints imposed by Western support for Ukraine. Partnerships with Iran and North Korea have enabled Moscow to secure supplies of drones, munitions, and other critical equipment, partially offsetting supply chain disruptions. For example, Iranian-made drones have become a staple in Russia’s military arsenal, demonstrating the Kremlin’s reliance on non-traditional allies for sustaining its war effort.

Geopolitically, Moscow has intensified its courtship of nations in the Global South, presenting itself as a counterbalance to Western hegemony. High-profile summits with African and Latin American leaders have emphasized promises of economic aid, military cooperation, and debt forgiveness, all aimed at securing support in international forums such as the United Nations. While these efforts have garnered some diplomatic victories, including abstentions in critical UN resolutions, they have done little to offset the broader erosion of Russia’s global influence.

Future Scenarios: Balancing Resilience and Vulnerability

As the conflict in Ukraine continues, Russia’s long-term strategy hinges on its ability to sustain resilience amidst mounting vulnerabilities. Key factors influencing the Kremlin’s trajectory include:

- Economic Sustainability: Without significant reforms, Russia’s fiscal reserves—currently estimated at $120 billion—may prove insufficient to sustain prolonged military expenditures and public subsidies. The depletion of these reserves could force deeper austerity measures, heightening social unrest and weakening Moscow’s political control.

- Alliances and Partnerships: Russia’s reliance on non-Western alliances will likely deepen, with countries such as China, India, and Turkey serving as critical lifelines. However, these relationships are transactional and subject to shifts in geopolitical dynamics, posing risks to their long-term viability.

- Technological Adaptation: The loss of access to Western technology, particularly semiconductors and aerospace components, remains a significant bottleneck. Russia’s domestic technology sector, hampered by a brain drain and limited R&D investment, is ill-equipped to fill the gap, necessitating further reliance on illicit procurement channels.

- Internal Stability: The Kremlin’s capacity to maintain internal stability will be tested by growing economic disparities and the erosion of middle-class livelihoods. While state-controlled media continues to propagate narratives of national resilience, dissent is becoming increasingly difficult to suppress, particularly among younger demographics.

In conclusion, the Kremlin’s countermeasures to Western pressure reveal a complex interplay of resilience and vulnerability. While Russia has demonstrated remarkable adaptability in certain domains, its long-term prospects remain deeply uncertain, contingent on both internal reforms and external geopolitical developments.

Enhancing Multilateral Collaboration for Sustainable Peace

The role of multilateral institutions in addressing the Ukraine conflict is pivotal, as these entities represent the collective will and cooperative potential of the global community. Yet, their efforts must evolve to meet the escalating complexities of modern warfare, political polarization, and economic interdependence. The mechanisms of such collaboration, while rooted in decades-old frameworks, require strategic recalibration to effectively mediate conflicts and sustain long-term peace.

Reimagining the Function of the United Nations

The United Nations, long viewed as the cornerstone of international conflict resolution, faces mounting criticism for its inability to enforce resolutions amidst power dynamics dictated by its permanent Security Council members. The ongoing impasse over Ukraine has highlighted the limits of consensus-driven frameworks, particularly when veto power undermines collective action. Reforming the Security Council, including restructuring voting privileges or expanding membership, has reemerged as a necessary yet contentious topic.

To compensate for institutional inertia, UN agencies like the World Food Programme (WFP) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have intensified efforts to address humanitarian dimensions of the conflict. These programs, while vital in mitigating immediate crises, remain underfunded. For example, as of 2023, the WFP reported a shortfall of $3.5 billion in its Ukraine-related operations, underscoring the urgent need for equitable burden-sharing among donor states.

Revitalizing the OSCE’s Conflict-Resolution Framework

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), uniquely positioned to address regional instability, has struggled to maintain its relevance. Its observer missions, including those stationed in Ukraine prior to 2022, often face operational constraints due to funding deficits and lack of unanimous support among member states. Strengthening the OSCE’s operational independence—by streamlining funding mechanisms or instituting non-veto-based decision-making—could enhance its ability to preempt crises.

The OSCE’s role in mediating ceasefires and monitoring peace agreements remains indispensable. However, its limited enforcement capacity highlights the need for greater integration with NATO and EU-led initiatives. Such synergies would allow the OSCE to leverage military expertise without compromising its neutrality.

Leveraging the European Union’s Economic and Diplomatic Influence

The European Union, as Ukraine’s largest donor and trading partner, wields unparalleled economic leverage over the region. The EU’s support for Ukraine has surpassed €50 billion since the onset of the war, encompassing military aid, humanitarian assistance, and infrastructure rebuilding. Expanding the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) initiatives could enable faster mobilization of resources for crisis response.

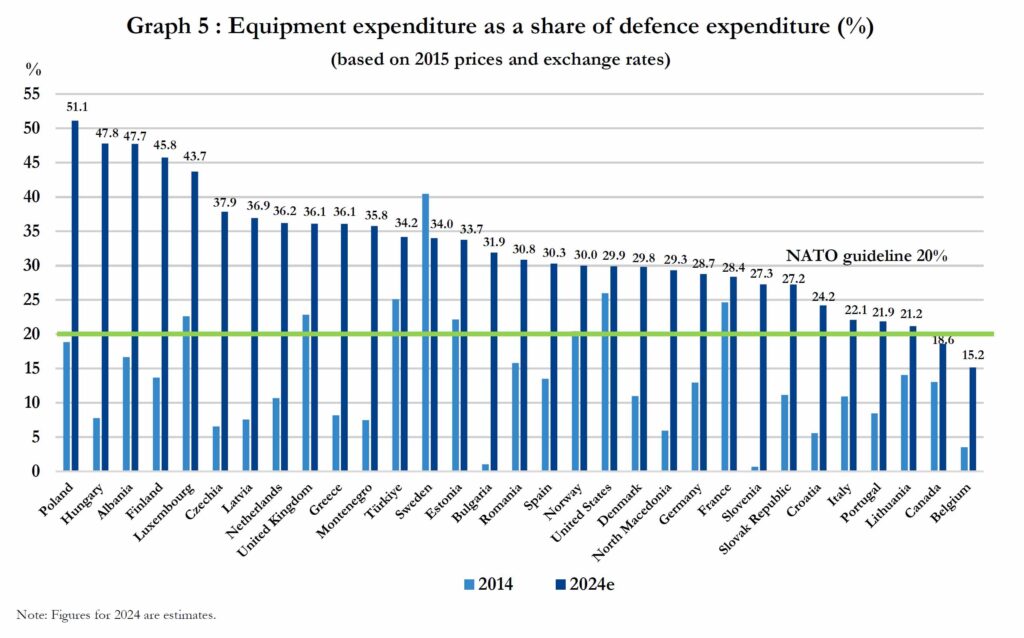

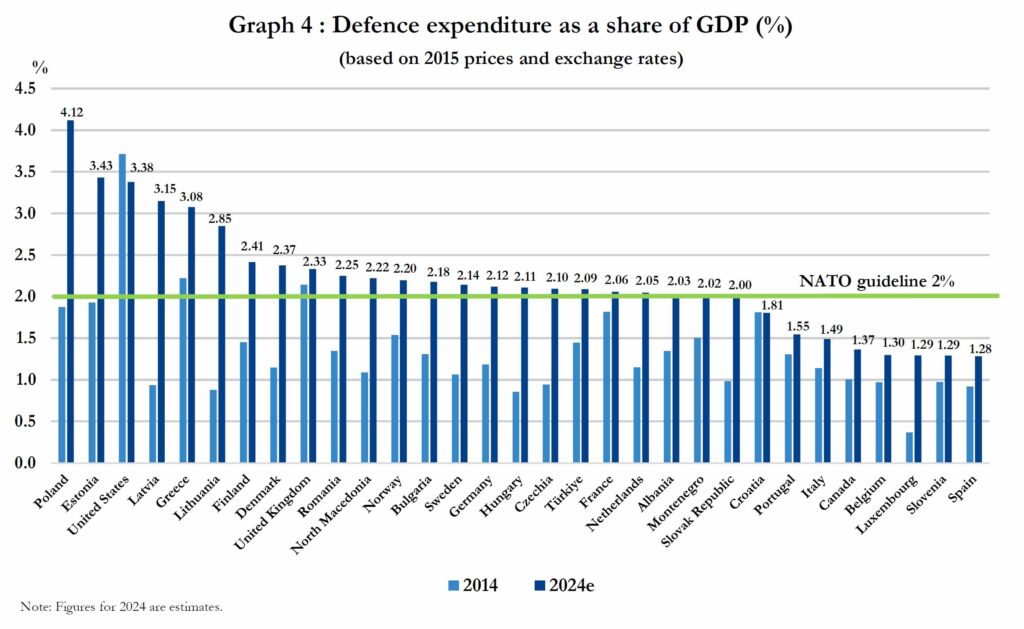

Nonetheless, internal divisions within the EU threaten to undermine its long-term strategic cohesion. Disparities in defense spending—ranging from Luxembourg’s 0.6% GDP allocation to Poland’s 4%—reflect broader disagreements over fiscal priorities. Addressing these discrepancies through standardized contributions to EU security initiatives would enhance both financial predictability and operational efficiency.

The Case for International Peacekeeping Forces

One of the most debated proposals for multilateral engagement is the deployment of an international peacekeeping force in Ukraine. While this concept has garnered support from Ukrainian leadership, its feasibility hinges on several critical factors:

- Operational Structure: A robust peacekeeping force must comprise contingents from neutral states to ensure impartiality. Potential contributors could include nations from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, thereby mitigating perceptions of Western bias.

- Mandate Clarity: The force must have a well-defined mandate, prioritizing civilian protection, infrastructure security, and facilitating humanitarian aid. Ambiguity in operational goals risks mission creep and reduced effectiveness.

- Resource Allocation: Funding such an initiative requires significant commitments from NATO, the EU, and non-aligned states. Current estimates suggest that a peacekeeping operation in Ukraine could cost upwards of $2 billion annually, depending on its size and scope.

- Political Backing: Securing United Nations General Assembly endorsement—given the likely Security Council deadlock—would provide moral legitimacy but not enforcement authority. Coordinated diplomacy remains essential to garner broader international support.

Shifting Alliances and Their Strategic Implications

The Ukraine conflict has catalyzed shifts in geopolitical alliances, creating opportunities for multilateral institutions to harness emerging partnerships. For instance, increased cooperation between NATO and Asia-Pacific allies, including Japan, South Korea, and Australia, underscores the global stakes of regional conflicts. Expanding these collaborations into broader multilateral frameworks could enhance collective security without diluting NATO’s primary focus.

Simultaneously, the strengthening of the Russia-China axis challenges the efficacy of Western-led multilateral institutions. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, coupled with its neutral stance on the Ukraine conflict, positions Beijing as a critical actor in global diplomacy. Engaging China in dialogue through platforms like the G20 may yield incremental progress on ancillary issues, such as food security and energy stability, even if broader conflict resolution remains elusive.

Creating a Resilient Framework for Global Peace

Achieving sustainable peace in Ukraine and beyond requires a paradigm shift in how multilateral institutions approach conflict resolution. Rather than reactive crisis management, these bodies must prioritize preventative diplomacy, integrated economic support, and inclusive governance structures. For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank could play more prominent roles by offering conditional financial assistance tied to conflict de-escalation measures.

Additionally, multilateral institutions must adapt to emerging threats, including cyber warfare and climate-induced instability. Integrating expertise from specialized organizations like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) could ensure more holistic responses to modern conflicts.

The future of multilateral engagement lies in its ability to bridge traditional power imbalances while fostering shared accountability. By embracing innovation and inclusivity, these institutions can transform global conflict resolution into a more equitable and effective endeavor.

Comprehensive Analysis of the Economic Transformation Triggered by NATO’s 5% Defense Mandate

Donald Trump’s proposal for NATO member states to allocate 5% of their GDP toward defense spending is poised to redefine the alliance’s financial and strategic framework. The dramatic escalation from the current 2% benchmark, which has already proven contentious, represents not just a fiscal challenge but a wholesale restructuring of national economic policies and priorities across all 32 NATO members. This directive, if implemented, would influence public finance, industrial production, labor markets, and societal dynamics on an unprecedented scale, necessitating a granular examination of its ramifications.

The proposed mandate would compel each member state to recalibrate its fiscal strategy to meet the 5% GDP threshold. For wealthier economies such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, this would translate into budgetary reallocations amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Germany, for instance, with a 2024 GDP forecast of $4.61 trillion, would need to raise its defense budget from approximately $97.7 billion to $230.5 billion—a $132.8 billion increase. This sum surpasses the total defense expenditures of some smaller NATO members combined and would necessitate significant cuts in public spending, higher taxation, or increased sovereign debt issuance.

Smaller economies, such as those of Latvia, Estonia, and Montenegro, would face comparatively greater fiscal strain relative to their GDPs. Latvia, with a projected GDP of $45.15 billion in 2024, would be required to raise its defense budget from $1.42 billion to $2.26 billion, a near doubling that could necessitate severe austerity measures or external financial assistance. These challenges underscore the asymmetrical impact of the 5% mandate, disproportionately affecting nations with limited fiscal flexibility.